User login

Weijen Chang, MD, SFHM, FAAP, is associate clinical professor of medicine and pediatrics at the University of California at San Diego School of Medicine, and a hospitalist at both UCSD Medical Center and Rady Children’s Hospital. He is a former member of Team Hospitalist and has served as The Hospitalist's pediatric editor since 2012.

Intravenous Immunoglobulin Most Common Retreatment Approach for Refractory Kawasaki Disease

Clinical question: How is refractory Kawasaki disease (rKD) treated in the United States?

Background: Kawasaki disease (KD) is an immunologically mediated disease of primarily small to medium-sized arteries. It is the most common cause of acquired heart disease in children in the United States.

The current standard of care for KD treatment is a single 2 g/kg dose of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), infused over 10 to 12 hours, accompanied by aspirin (80 to 100 mg/kg/day by mouth in four divided doses). Fevers persistent more than 36 hours after initial treatment represent refractory Kawasaki disease (rKD). There are no current national guidelines or standards for rKD treatment, although a 2004 joint statement from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American Heart Association suggested a second dose of IVIG for rKD.

Study design: Multicenter, retrospective, cross-sectional study.

Setting: Forty freestanding children’s hospitals.

Synopsis: Researchers examined data obtained from the Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS), a clinical and financial database of care provided at 43 nonprofit, freestanding children’s hospitals in the United States. Data from 40 of these hospitals were deemed complete enough for analysis and were collected from Jan. 1, 2005, to June 30, 2009. Subjects were included if they received at least one dose of IVIG and had a principal diagnosis of KD. To be considered rKD, the subject must have received additional treatment after the initial diagnosis of rKD.

The most commonly used treatment after initial IVIG treatment was retreatment with IVIG (65%), followed by intravenous methylprednisolone (27%), then infliximab (8%). Significant regional variation was observed, with hospitals in the Northeast using methylprednisolone most frequently for rKD (55%). Infliximab was used at a much higher frequency in the West (29%) compared with other regions.

Bottom line: Retreatment with IVIG is the most common treatment for rKD, but significant regional variation exists, possibly due to the influence of regional experts.

Citation: Ghelani SJ, Pastor W, Parikh K. Demographic and treatment variability of refractory Kawasaki Disease: a multicenter analysis from 2005 to 2009. Hospital Pediatrics. 2012;2:71-76.

Reviewed by Pediatric Editor Weijen Chang, MD, SFHM, FAAP, associate clinical professor of medicine and pediatrics at the University of California at San Diego School of Medicine, and a hospitalist at both UCSD Medical Center and Rady Children’s Hospital.

Clinical question: How is refractory Kawasaki disease (rKD) treated in the United States?

Background: Kawasaki disease (KD) is an immunologically mediated disease of primarily small to medium-sized arteries. It is the most common cause of acquired heart disease in children in the United States.

The current standard of care for KD treatment is a single 2 g/kg dose of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), infused over 10 to 12 hours, accompanied by aspirin (80 to 100 mg/kg/day by mouth in four divided doses). Fevers persistent more than 36 hours after initial treatment represent refractory Kawasaki disease (rKD). There are no current national guidelines or standards for rKD treatment, although a 2004 joint statement from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American Heart Association suggested a second dose of IVIG for rKD.

Study design: Multicenter, retrospective, cross-sectional study.

Setting: Forty freestanding children’s hospitals.

Synopsis: Researchers examined data obtained from the Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS), a clinical and financial database of care provided at 43 nonprofit, freestanding children’s hospitals in the United States. Data from 40 of these hospitals were deemed complete enough for analysis and were collected from Jan. 1, 2005, to June 30, 2009. Subjects were included if they received at least one dose of IVIG and had a principal diagnosis of KD. To be considered rKD, the subject must have received additional treatment after the initial diagnosis of rKD.

The most commonly used treatment after initial IVIG treatment was retreatment with IVIG (65%), followed by intravenous methylprednisolone (27%), then infliximab (8%). Significant regional variation was observed, with hospitals in the Northeast using methylprednisolone most frequently for rKD (55%). Infliximab was used at a much higher frequency in the West (29%) compared with other regions.

Bottom line: Retreatment with IVIG is the most common treatment for rKD, but significant regional variation exists, possibly due to the influence of regional experts.

Citation: Ghelani SJ, Pastor W, Parikh K. Demographic and treatment variability of refractory Kawasaki Disease: a multicenter analysis from 2005 to 2009. Hospital Pediatrics. 2012;2:71-76.

Reviewed by Pediatric Editor Weijen Chang, MD, SFHM, FAAP, associate clinical professor of medicine and pediatrics at the University of California at San Diego School of Medicine, and a hospitalist at both UCSD Medical Center and Rady Children’s Hospital.

Clinical question: How is refractory Kawasaki disease (rKD) treated in the United States?

Background: Kawasaki disease (KD) is an immunologically mediated disease of primarily small to medium-sized arteries. It is the most common cause of acquired heart disease in children in the United States.

The current standard of care for KD treatment is a single 2 g/kg dose of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), infused over 10 to 12 hours, accompanied by aspirin (80 to 100 mg/kg/day by mouth in four divided doses). Fevers persistent more than 36 hours after initial treatment represent refractory Kawasaki disease (rKD). There are no current national guidelines or standards for rKD treatment, although a 2004 joint statement from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American Heart Association suggested a second dose of IVIG for rKD.

Study design: Multicenter, retrospective, cross-sectional study.

Setting: Forty freestanding children’s hospitals.

Synopsis: Researchers examined data obtained from the Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS), a clinical and financial database of care provided at 43 nonprofit, freestanding children’s hospitals in the United States. Data from 40 of these hospitals were deemed complete enough for analysis and were collected from Jan. 1, 2005, to June 30, 2009. Subjects were included if they received at least one dose of IVIG and had a principal diagnosis of KD. To be considered rKD, the subject must have received additional treatment after the initial diagnosis of rKD.

The most commonly used treatment after initial IVIG treatment was retreatment with IVIG (65%), followed by intravenous methylprednisolone (27%), then infliximab (8%). Significant regional variation was observed, with hospitals in the Northeast using methylprednisolone most frequently for rKD (55%). Infliximab was used at a much higher frequency in the West (29%) compared with other regions.

Bottom line: Retreatment with IVIG is the most common treatment for rKD, but significant regional variation exists, possibly due to the influence of regional experts.

Citation: Ghelani SJ, Pastor W, Parikh K. Demographic and treatment variability of refractory Kawasaki Disease: a multicenter analysis from 2005 to 2009. Hospital Pediatrics. 2012;2:71-76.

Reviewed by Pediatric Editor Weijen Chang, MD, SFHM, FAAP, associate clinical professor of medicine and pediatrics at the University of California at San Diego School of Medicine, and a hospitalist at both UCSD Medical Center and Rady Children’s Hospital.

Observation Status Designation in Pediatric Hospitals Is Costly

Clinical question: What are the costs associated with observation-status hospital stays compared to inpatient-status stays in pediatric hospitals?

Background: Observation status is a designation for hospitalizations that are typically shorter than 48 hours and do not meet criteria for inpatient status. It is considered to be outpatient for evaluation and management (E/M) coding. A designation of observation status for a hospital stay can have significant effects on out-of-pocket costs for patients and reimbursements to physicians and hospitals. It also can affect readmission and length-of-stay data, as observation-status hospital stays are often excluded from a hospital’s inpatient data.

Study design: Multicenter retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Thirty-three freestanding children’s hospitals.

Synopsis: Researchers reviewed data obtained from the Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS), which contains demographic and resource utilization date from 43 freestanding children’s hospitals in the U.S. Resource utilization data were reviewed from 33 of 43 hospitals in PHIS that reported data regarding observation- versus inpatient-status stays. Data were then limited to observation-status stays £2 days, which made up 97.8% of all observation-status stays. These were then compared to a corresponding cohort of inpatient-status stays of £2 days (47.5% of inpatient-status stays), excluding any patient who had spent time in an ICU.

Hospitalization costs were analyzed and separated into room and nonroom costs, as well as in aggregate. These were further subdivided into costs for four common diagnoses (asthma, gastroenteritis, bronchiolitis, and seizure) and were risk-adjusted.

Observation status was used variably between hospitals (2% to 45%) and within hospitals. There was significant overlap in costs of observation-status and inpatient-status stays, which persisted when accounting for nonroom costs and within the diagnosis subgroups. Although average severity-adjusted costs for observation-status stays were consistently less than those for inpatient-status stays, the dollar amounts were small.

Bottom line: Observation-status designation is used inconsistently in pediatric hospitals, and their costs overlap substantially with inpatient-status stays.

Citation: Fieldston ES, Shah SS, Hall M. Resource utilization for observation-status stays at children’s hospitals. Pediatrics. 2013;131;1050-1058.

Reviewed by Pediatric Editor Weijen Chang, MD, SFHM, FACP, associate clinical professor of medicine and pediatrics at the University of California at San Diego School of Medicine, and a hospitalist at both UCSD Medical Center and Rady Children’s Hospital.

Clinical question: What are the costs associated with observation-status hospital stays compared to inpatient-status stays in pediatric hospitals?

Background: Observation status is a designation for hospitalizations that are typically shorter than 48 hours and do not meet criteria for inpatient status. It is considered to be outpatient for evaluation and management (E/M) coding. A designation of observation status for a hospital stay can have significant effects on out-of-pocket costs for patients and reimbursements to physicians and hospitals. It also can affect readmission and length-of-stay data, as observation-status hospital stays are often excluded from a hospital’s inpatient data.

Study design: Multicenter retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Thirty-three freestanding children’s hospitals.

Synopsis: Researchers reviewed data obtained from the Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS), which contains demographic and resource utilization date from 43 freestanding children’s hospitals in the U.S. Resource utilization data were reviewed from 33 of 43 hospitals in PHIS that reported data regarding observation- versus inpatient-status stays. Data were then limited to observation-status stays £2 days, which made up 97.8% of all observation-status stays. These were then compared to a corresponding cohort of inpatient-status stays of £2 days (47.5% of inpatient-status stays), excluding any patient who had spent time in an ICU.

Hospitalization costs were analyzed and separated into room and nonroom costs, as well as in aggregate. These were further subdivided into costs for four common diagnoses (asthma, gastroenteritis, bronchiolitis, and seizure) and were risk-adjusted.

Observation status was used variably between hospitals (2% to 45%) and within hospitals. There was significant overlap in costs of observation-status and inpatient-status stays, which persisted when accounting for nonroom costs and within the diagnosis subgroups. Although average severity-adjusted costs for observation-status stays were consistently less than those for inpatient-status stays, the dollar amounts were small.

Bottom line: Observation-status designation is used inconsistently in pediatric hospitals, and their costs overlap substantially with inpatient-status stays.

Citation: Fieldston ES, Shah SS, Hall M. Resource utilization for observation-status stays at children’s hospitals. Pediatrics. 2013;131;1050-1058.

Reviewed by Pediatric Editor Weijen Chang, MD, SFHM, FACP, associate clinical professor of medicine and pediatrics at the University of California at San Diego School of Medicine, and a hospitalist at both UCSD Medical Center and Rady Children’s Hospital.

Clinical question: What are the costs associated with observation-status hospital stays compared to inpatient-status stays in pediatric hospitals?

Background: Observation status is a designation for hospitalizations that are typically shorter than 48 hours and do not meet criteria for inpatient status. It is considered to be outpatient for evaluation and management (E/M) coding. A designation of observation status for a hospital stay can have significant effects on out-of-pocket costs for patients and reimbursements to physicians and hospitals. It also can affect readmission and length-of-stay data, as observation-status hospital stays are often excluded from a hospital’s inpatient data.

Study design: Multicenter retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Thirty-three freestanding children’s hospitals.

Synopsis: Researchers reviewed data obtained from the Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS), which contains demographic and resource utilization date from 43 freestanding children’s hospitals in the U.S. Resource utilization data were reviewed from 33 of 43 hospitals in PHIS that reported data regarding observation- versus inpatient-status stays. Data were then limited to observation-status stays £2 days, which made up 97.8% of all observation-status stays. These were then compared to a corresponding cohort of inpatient-status stays of £2 days (47.5% of inpatient-status stays), excluding any patient who had spent time in an ICU.

Hospitalization costs were analyzed and separated into room and nonroom costs, as well as in aggregate. These were further subdivided into costs for four common diagnoses (asthma, gastroenteritis, bronchiolitis, and seizure) and were risk-adjusted.

Observation status was used variably between hospitals (2% to 45%) and within hospitals. There was significant overlap in costs of observation-status and inpatient-status stays, which persisted when accounting for nonroom costs and within the diagnosis subgroups. Although average severity-adjusted costs for observation-status stays were consistently less than those for inpatient-status stays, the dollar amounts were small.

Bottom line: Observation-status designation is used inconsistently in pediatric hospitals, and their costs overlap substantially with inpatient-status stays.

Citation: Fieldston ES, Shah SS, Hall M. Resource utilization for observation-status stays at children’s hospitals. Pediatrics. 2013;131;1050-1058.

Reviewed by Pediatric Editor Weijen Chang, MD, SFHM, FACP, associate clinical professor of medicine and pediatrics at the University of California at San Diego School of Medicine, and a hospitalist at both UCSD Medical Center and Rady Children’s Hospital.

Pediatric Hospital Medicine Aims to Define Itself

Legend has it that Alexander the Great once was confronted with an intricate knot tying up a sacred ox cart in the palace of the Phrygians, whom he was trying to conquer. When his attempts to untie the knot proved unsuccessful, he drew his sword and sliced it in half, thus providing a rapid if inelegant solution.

Pediatric hospital medicine (PHM) now finds itself facing a similar dilemma in its attempts to define its “kingdom.” The question: Who will become citizens of this kingdom—and who will be left outside the gates? And will this intricate knot be unraveled or simply cut?

In some ways, the mere posing of this question signifies the success PHM has forged for itself over the past decade. At its core, the question of how to define the identity, and thus the training, of a pediatric hospitalist is rooted in noble ideals: excellence in the management of hospitalized children, robust training in quality improvement, patient safety, and cost-effective care.1 Yet this question also stirs up more base feelings frequently articulated in many a physician lounge: territoriality, inadequacy, feeling excluded.

Nevertheless, the question must be answered.

In many ways, the situation in which PHM finds itself mirrors the dilemma facing pediatrics itself in its infancy. As Borden Veeder, the first president of the American Board of Pediatrics (ABP), wrote in the 1930s, “There were no legal or medical requirements relating to the training and education of specialists—all a man licensed to practice medicine had to do was to announce himself as a surgeon, internist, pediatrician, etc., as he preferred.”2 In 1933, the ABP was incorporated, with representatives from the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), the American Medical Association (AMA) section on pediatrics, and the American Pediatric Society.

Facing a similar state of confusion, hospitalist leaders of the PHM community in 2010 formed the Strategic Planning Committee (STP) to evaluate training and certification options for PHM as a distinct discipline.3 Co-chairs of the STP Committee were chosen by consensus from a group composed of one representative each from the AAP Section on Hospital Medicine (AAP SOHM), the Academic Pediatric Association (APA), and SHM. The STP identified various training and/or certification options that could define PHM as a subspecialty. A survey with these options was distributed to the PHM community via the listservs of the APA, the AAP SOHM, and the AAP. The results:3

- 33% of respondents preferred Recognition of Focused Practice through the American Board of Internal Medicine’s (ABIM) Maintenance of Certification (MOC);

- 30% preferred a two-year fellowship; and

- 17% suggested an HM track within pediatric residency.

Yet at the PHM Leaders Conference in Chapel Hill, N.C., in April, “there was overwhelming consensus that an MOC program could not provide the rigor to insure [sic] that all pediatric hospitalists would meet a standard.”4 Further, “there was overwhelming consensus that a standardized training program resulting in certification was the best option to assure adequate training in the PHM Core Competencies and provide the public with a meaningful definition of a pediatric hospitalist” and “that the duration of such training should be two years.” Why, one might ask, would those present feel so strongly that the MOC model would be inadequate?

Many concerns regarding MOC were voiced, including whether MOC addresses a knowledge gap after residency (which it does to some extent through ongoing recertification requirements), whether it ensures public trust (but it had “positive potential”), and whether it addressed core competencies (to which the leadership present answered “yes, if rigorous”).4

The perception that the Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine (FPHM) MOC was “not a successful model so far in adult hospital medicine” seemed to weigh heavily on the minds of those in attendance. This perception may have arisen from data showing a somewhat low number of adult hospitalists (363 completed, 527 in process) having successfully completed the FPHM MOC to date. Of note, the possibility of a FPHM MOC for PHM was considered a “non-starter” by the ABP representatives, who in turn attributed this determination to the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS).5

There are, of course, many reasons for the low turnout for adult FPHM MOC. Candidates must have been previously certified in internal medicine of family medicine, and thus entry into the FPHM MOC would only arise at recertification or if one decided to seek FPHM certification “early”—that is, prior to the need for recertification. Being not only a Procrastination Club president but also a client, I was not among the 67 virtuous hospitalists who were among the first class of FPHM diplomates in 2011.6 The FPHM MOC also initially was more rigorous than the traditional IM recertification, in that it required completion of a practice-improvement module (PIM) every three years versus every 10 years (in 2014, both the traditional IM and FPHM MOC programs will require PIM completion every 5 years). Without a clearly mandated requirement from most HM groups, at the inception of the FPHM MOC one would be entering a more rigorous recertification process without a clear benefit.

This lack of a requirement from adult HM groups for completion or entry into the FPHM MOC, in turn, arises from a straightforward issue: workforce. Requiring all hospitalists in your HM group to have completed or entered FPHM MOC is a bar most directors and chiefs are not prepared to raise given its potential to shrink their applicant pool. With only 32 to 35 graduates of pediatric HM fellowship programs yearly, workforce issues should clearly be of concern to the PHM community given the current estimates that pediatric hospitalists number anywhere from 1,500 to 3,000.6,7

Is the adult FPHM MOC process perfect? Nothing created by so many committees and professional societies could ever be, but as a first iteration, it certainly created a relatively sturdy straw man. Could the PHM community create a FPHM MOC upon this model that was refined and tailored to their needs? Creating and requiring completion of a robust PHM-specific curriculum via required self-evaluation modules, requiring not only patient encounter thresholds but also evidence of quality care, and developing PIMs specific to PHM would all go a long way to making a FPHM MOC an acceptable alternative for pediatric hospitalist “designation.”

In any case, the gauntlet seems to have been thrown down already in Chapel Hill in favor of a two-year fellowship leading to certification. I admire those present for advocating a training and certification that provides the least compromise in defining the path of future pediatric hospitalists. But I suspect that the answer to the problem of PHM’s future may not be so simple as a single sharp-edged solution and might lie in a more complex array of options for future pediatric hospitalists.

Dr. Chang is pediatric editor of The Hospitalist. He is associate clinical professor of medicine and pediatrics at the University of California at San Diego (UCSD) School of Medicine, and a hospitalist at both UCSD Medical Center and Rady Children’s Hospital. Send comments and questions to wwch@ucsd.edu.

References

- Maniscalco J, Fisher ES. Pediatric hospital medicine and education: why we can’t stand still. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167:412-413.

- Brownlee RC. The American Board of Pediatrics: its origin and early history. Pediatrics. 1994;94:732-735.

- Maloney CG, Mendez SS, Quinonez RA, et al. The Strategic Planning Committee report: the first step in a journey to recognize pediatric hospital medicine as a distinct discipline. Hospital Pediatrics. 2012;2:187-190.

- Strategic Planning Committee. Strategic planning for the future of pediatric hospital medicine. Strategic Planning Committee website. Available at: http://stpcommittee.blogspot.com/2013/04/phm-leadership-conference-april-4-5.htmlfiles/97/phm-leadership-conference-april-4-5.html. Accessed July 4, 2013.

- Fisher ES. (2013) Email sent to Chang WW. 25 June.

- Carris J. Defining moment: focused practice in HM. The Hospitalist website. Available at: http://www.the-hospitalist.org/details/article/1018793/Defining_Moment_Focused_Practice_in_HM.html. Accessed June 15, 2013.

- American Academy of Pediatrics. PHM fellowship info. American Academy of Pediatrics website. Available at: http://www.aap.org/en-us/about-the-aap/Committees-Councils-Sections/Section-on-Hospital-Medicine.html. Accessed June 15, 2013.

- Rauch DA, Lye PS, Carlson D, et al. Pediatric hospital medicine: a strategic planning roundtable to chart the future. J Hosp Med. 2012;7:329-334.

Legend has it that Alexander the Great once was confronted with an intricate knot tying up a sacred ox cart in the palace of the Phrygians, whom he was trying to conquer. When his attempts to untie the knot proved unsuccessful, he drew his sword and sliced it in half, thus providing a rapid if inelegant solution.

Pediatric hospital medicine (PHM) now finds itself facing a similar dilemma in its attempts to define its “kingdom.” The question: Who will become citizens of this kingdom—and who will be left outside the gates? And will this intricate knot be unraveled or simply cut?

In some ways, the mere posing of this question signifies the success PHM has forged for itself over the past decade. At its core, the question of how to define the identity, and thus the training, of a pediatric hospitalist is rooted in noble ideals: excellence in the management of hospitalized children, robust training in quality improvement, patient safety, and cost-effective care.1 Yet this question also stirs up more base feelings frequently articulated in many a physician lounge: territoriality, inadequacy, feeling excluded.

Nevertheless, the question must be answered.

In many ways, the situation in which PHM finds itself mirrors the dilemma facing pediatrics itself in its infancy. As Borden Veeder, the first president of the American Board of Pediatrics (ABP), wrote in the 1930s, “There were no legal or medical requirements relating to the training and education of specialists—all a man licensed to practice medicine had to do was to announce himself as a surgeon, internist, pediatrician, etc., as he preferred.”2 In 1933, the ABP was incorporated, with representatives from the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), the American Medical Association (AMA) section on pediatrics, and the American Pediatric Society.

Facing a similar state of confusion, hospitalist leaders of the PHM community in 2010 formed the Strategic Planning Committee (STP) to evaluate training and certification options for PHM as a distinct discipline.3 Co-chairs of the STP Committee were chosen by consensus from a group composed of one representative each from the AAP Section on Hospital Medicine (AAP SOHM), the Academic Pediatric Association (APA), and SHM. The STP identified various training and/or certification options that could define PHM as a subspecialty. A survey with these options was distributed to the PHM community via the listservs of the APA, the AAP SOHM, and the AAP. The results:3

- 33% of respondents preferred Recognition of Focused Practice through the American Board of Internal Medicine’s (ABIM) Maintenance of Certification (MOC);

- 30% preferred a two-year fellowship; and

- 17% suggested an HM track within pediatric residency.

Yet at the PHM Leaders Conference in Chapel Hill, N.C., in April, “there was overwhelming consensus that an MOC program could not provide the rigor to insure [sic] that all pediatric hospitalists would meet a standard.”4 Further, “there was overwhelming consensus that a standardized training program resulting in certification was the best option to assure adequate training in the PHM Core Competencies and provide the public with a meaningful definition of a pediatric hospitalist” and “that the duration of such training should be two years.” Why, one might ask, would those present feel so strongly that the MOC model would be inadequate?

Many concerns regarding MOC were voiced, including whether MOC addresses a knowledge gap after residency (which it does to some extent through ongoing recertification requirements), whether it ensures public trust (but it had “positive potential”), and whether it addressed core competencies (to which the leadership present answered “yes, if rigorous”).4

The perception that the Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine (FPHM) MOC was “not a successful model so far in adult hospital medicine” seemed to weigh heavily on the minds of those in attendance. This perception may have arisen from data showing a somewhat low number of adult hospitalists (363 completed, 527 in process) having successfully completed the FPHM MOC to date. Of note, the possibility of a FPHM MOC for PHM was considered a “non-starter” by the ABP representatives, who in turn attributed this determination to the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS).5

There are, of course, many reasons for the low turnout for adult FPHM MOC. Candidates must have been previously certified in internal medicine of family medicine, and thus entry into the FPHM MOC would only arise at recertification or if one decided to seek FPHM certification “early”—that is, prior to the need for recertification. Being not only a Procrastination Club president but also a client, I was not among the 67 virtuous hospitalists who were among the first class of FPHM diplomates in 2011.6 The FPHM MOC also initially was more rigorous than the traditional IM recertification, in that it required completion of a practice-improvement module (PIM) every three years versus every 10 years (in 2014, both the traditional IM and FPHM MOC programs will require PIM completion every 5 years). Without a clearly mandated requirement from most HM groups, at the inception of the FPHM MOC one would be entering a more rigorous recertification process without a clear benefit.

This lack of a requirement from adult HM groups for completion or entry into the FPHM MOC, in turn, arises from a straightforward issue: workforce. Requiring all hospitalists in your HM group to have completed or entered FPHM MOC is a bar most directors and chiefs are not prepared to raise given its potential to shrink their applicant pool. With only 32 to 35 graduates of pediatric HM fellowship programs yearly, workforce issues should clearly be of concern to the PHM community given the current estimates that pediatric hospitalists number anywhere from 1,500 to 3,000.6,7

Is the adult FPHM MOC process perfect? Nothing created by so many committees and professional societies could ever be, but as a first iteration, it certainly created a relatively sturdy straw man. Could the PHM community create a FPHM MOC upon this model that was refined and tailored to their needs? Creating and requiring completion of a robust PHM-specific curriculum via required self-evaluation modules, requiring not only patient encounter thresholds but also evidence of quality care, and developing PIMs specific to PHM would all go a long way to making a FPHM MOC an acceptable alternative for pediatric hospitalist “designation.”

In any case, the gauntlet seems to have been thrown down already in Chapel Hill in favor of a two-year fellowship leading to certification. I admire those present for advocating a training and certification that provides the least compromise in defining the path of future pediatric hospitalists. But I suspect that the answer to the problem of PHM’s future may not be so simple as a single sharp-edged solution and might lie in a more complex array of options for future pediatric hospitalists.

Dr. Chang is pediatric editor of The Hospitalist. He is associate clinical professor of medicine and pediatrics at the University of California at San Diego (UCSD) School of Medicine, and a hospitalist at both UCSD Medical Center and Rady Children’s Hospital. Send comments and questions to wwch@ucsd.edu.

References

- Maniscalco J, Fisher ES. Pediatric hospital medicine and education: why we can’t stand still. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167:412-413.

- Brownlee RC. The American Board of Pediatrics: its origin and early history. Pediatrics. 1994;94:732-735.

- Maloney CG, Mendez SS, Quinonez RA, et al. The Strategic Planning Committee report: the first step in a journey to recognize pediatric hospital medicine as a distinct discipline. Hospital Pediatrics. 2012;2:187-190.

- Strategic Planning Committee. Strategic planning for the future of pediatric hospital medicine. Strategic Planning Committee website. Available at: http://stpcommittee.blogspot.com/2013/04/phm-leadership-conference-april-4-5.htmlfiles/97/phm-leadership-conference-april-4-5.html. Accessed July 4, 2013.

- Fisher ES. (2013) Email sent to Chang WW. 25 June.

- Carris J. Defining moment: focused practice in HM. The Hospitalist website. Available at: http://www.the-hospitalist.org/details/article/1018793/Defining_Moment_Focused_Practice_in_HM.html. Accessed June 15, 2013.

- American Academy of Pediatrics. PHM fellowship info. American Academy of Pediatrics website. Available at: http://www.aap.org/en-us/about-the-aap/Committees-Councils-Sections/Section-on-Hospital-Medicine.html. Accessed June 15, 2013.

- Rauch DA, Lye PS, Carlson D, et al. Pediatric hospital medicine: a strategic planning roundtable to chart the future. J Hosp Med. 2012;7:329-334.

Legend has it that Alexander the Great once was confronted with an intricate knot tying up a sacred ox cart in the palace of the Phrygians, whom he was trying to conquer. When his attempts to untie the knot proved unsuccessful, he drew his sword and sliced it in half, thus providing a rapid if inelegant solution.

Pediatric hospital medicine (PHM) now finds itself facing a similar dilemma in its attempts to define its “kingdom.” The question: Who will become citizens of this kingdom—and who will be left outside the gates? And will this intricate knot be unraveled or simply cut?

In some ways, the mere posing of this question signifies the success PHM has forged for itself over the past decade. At its core, the question of how to define the identity, and thus the training, of a pediatric hospitalist is rooted in noble ideals: excellence in the management of hospitalized children, robust training in quality improvement, patient safety, and cost-effective care.1 Yet this question also stirs up more base feelings frequently articulated in many a physician lounge: territoriality, inadequacy, feeling excluded.

Nevertheless, the question must be answered.

In many ways, the situation in which PHM finds itself mirrors the dilemma facing pediatrics itself in its infancy. As Borden Veeder, the first president of the American Board of Pediatrics (ABP), wrote in the 1930s, “There were no legal or medical requirements relating to the training and education of specialists—all a man licensed to practice medicine had to do was to announce himself as a surgeon, internist, pediatrician, etc., as he preferred.”2 In 1933, the ABP was incorporated, with representatives from the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), the American Medical Association (AMA) section on pediatrics, and the American Pediatric Society.

Facing a similar state of confusion, hospitalist leaders of the PHM community in 2010 formed the Strategic Planning Committee (STP) to evaluate training and certification options for PHM as a distinct discipline.3 Co-chairs of the STP Committee were chosen by consensus from a group composed of one representative each from the AAP Section on Hospital Medicine (AAP SOHM), the Academic Pediatric Association (APA), and SHM. The STP identified various training and/or certification options that could define PHM as a subspecialty. A survey with these options was distributed to the PHM community via the listservs of the APA, the AAP SOHM, and the AAP. The results:3

- 33% of respondents preferred Recognition of Focused Practice through the American Board of Internal Medicine’s (ABIM) Maintenance of Certification (MOC);

- 30% preferred a two-year fellowship; and

- 17% suggested an HM track within pediatric residency.

Yet at the PHM Leaders Conference in Chapel Hill, N.C., in April, “there was overwhelming consensus that an MOC program could not provide the rigor to insure [sic] that all pediatric hospitalists would meet a standard.”4 Further, “there was overwhelming consensus that a standardized training program resulting in certification was the best option to assure adequate training in the PHM Core Competencies and provide the public with a meaningful definition of a pediatric hospitalist” and “that the duration of such training should be two years.” Why, one might ask, would those present feel so strongly that the MOC model would be inadequate?

Many concerns regarding MOC were voiced, including whether MOC addresses a knowledge gap after residency (which it does to some extent through ongoing recertification requirements), whether it ensures public trust (but it had “positive potential”), and whether it addressed core competencies (to which the leadership present answered “yes, if rigorous”).4

The perception that the Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine (FPHM) MOC was “not a successful model so far in adult hospital medicine” seemed to weigh heavily on the minds of those in attendance. This perception may have arisen from data showing a somewhat low number of adult hospitalists (363 completed, 527 in process) having successfully completed the FPHM MOC to date. Of note, the possibility of a FPHM MOC for PHM was considered a “non-starter” by the ABP representatives, who in turn attributed this determination to the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS).5

There are, of course, many reasons for the low turnout for adult FPHM MOC. Candidates must have been previously certified in internal medicine of family medicine, and thus entry into the FPHM MOC would only arise at recertification or if one decided to seek FPHM certification “early”—that is, prior to the need for recertification. Being not only a Procrastination Club president but also a client, I was not among the 67 virtuous hospitalists who were among the first class of FPHM diplomates in 2011.6 The FPHM MOC also initially was more rigorous than the traditional IM recertification, in that it required completion of a practice-improvement module (PIM) every three years versus every 10 years (in 2014, both the traditional IM and FPHM MOC programs will require PIM completion every 5 years). Without a clearly mandated requirement from most HM groups, at the inception of the FPHM MOC one would be entering a more rigorous recertification process without a clear benefit.

This lack of a requirement from adult HM groups for completion or entry into the FPHM MOC, in turn, arises from a straightforward issue: workforce. Requiring all hospitalists in your HM group to have completed or entered FPHM MOC is a bar most directors and chiefs are not prepared to raise given its potential to shrink their applicant pool. With only 32 to 35 graduates of pediatric HM fellowship programs yearly, workforce issues should clearly be of concern to the PHM community given the current estimates that pediatric hospitalists number anywhere from 1,500 to 3,000.6,7

Is the adult FPHM MOC process perfect? Nothing created by so many committees and professional societies could ever be, but as a first iteration, it certainly created a relatively sturdy straw man. Could the PHM community create a FPHM MOC upon this model that was refined and tailored to their needs? Creating and requiring completion of a robust PHM-specific curriculum via required self-evaluation modules, requiring not only patient encounter thresholds but also evidence of quality care, and developing PIMs specific to PHM would all go a long way to making a FPHM MOC an acceptable alternative for pediatric hospitalist “designation.”

In any case, the gauntlet seems to have been thrown down already in Chapel Hill in favor of a two-year fellowship leading to certification. I admire those present for advocating a training and certification that provides the least compromise in defining the path of future pediatric hospitalists. But I suspect that the answer to the problem of PHM’s future may not be so simple as a single sharp-edged solution and might lie in a more complex array of options for future pediatric hospitalists.

Dr. Chang is pediatric editor of The Hospitalist. He is associate clinical professor of medicine and pediatrics at the University of California at San Diego (UCSD) School of Medicine, and a hospitalist at both UCSD Medical Center and Rady Children’s Hospital. Send comments and questions to wwch@ucsd.edu.

References

- Maniscalco J, Fisher ES. Pediatric hospital medicine and education: why we can’t stand still. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167:412-413.

- Brownlee RC. The American Board of Pediatrics: its origin and early history. Pediatrics. 1994;94:732-735.

- Maloney CG, Mendez SS, Quinonez RA, et al. The Strategic Planning Committee report: the first step in a journey to recognize pediatric hospital medicine as a distinct discipline. Hospital Pediatrics. 2012;2:187-190.

- Strategic Planning Committee. Strategic planning for the future of pediatric hospital medicine. Strategic Planning Committee website. Available at: http://stpcommittee.blogspot.com/2013/04/phm-leadership-conference-april-4-5.htmlfiles/97/phm-leadership-conference-april-4-5.html. Accessed July 4, 2013.

- Fisher ES. (2013) Email sent to Chang WW. 25 June.

- Carris J. Defining moment: focused practice in HM. The Hospitalist website. Available at: http://www.the-hospitalist.org/details/article/1018793/Defining_Moment_Focused_Practice_in_HM.html. Accessed June 15, 2013.

- American Academy of Pediatrics. PHM fellowship info. American Academy of Pediatrics website. Available at: http://www.aap.org/en-us/about-the-aap/Committees-Councils-Sections/Section-on-Hospital-Medicine.html. Accessed June 15, 2013.

- Rauch DA, Lye PS, Carlson D, et al. Pediatric hospital medicine: a strategic planning roundtable to chart the future. J Hosp Med. 2012;7:329-334.

HM12's Clinical Pearls

SESSION

DVT Prophylaxis: Don’t Forget the Pediatric Patients

Most would agree that hospitalists have seen more thrombosis in children over the past decade, and although it isn’t known why, it is likely due to multifactorial causes, said Leslie Raffini, MD, MSCE, director of the Hemostasis and Thrombosis Center at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

Central venous catheters remain a significant risk factor for venous thromboembolism (VTE), and our knowledge of inherited risk factors has expanded in recent years. While it is likely that inherited risk factors increase the risk of thrombosis in children, the question of testing has engendered debate, due in large part to the lack of clear benefit of that information in the majority of situations.

“The decision to test should be made on an individual basis, after counseling,” said Dr. Raffini. “Results should be interpreted by an experienced physician with adolescent females most likely to benefit from the testing. There are no recommendations for what to do with pediatric patients” despite the fact that this is an important cause of morbidity in high-risk patients.

Dr. Raffini described efforts at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia that led to a VTE prophylaxis guideline. Successful implementation of the guideline required significant multidisciplinary collaboration, and an analysis of outcomes is under way.

SESSION

Updates from the 9th ACCP Antithrombotic Therapy Guidelines

The evidence-based, rapid-fire presentation by Catherine Curley, MD, of MetroHealth Medical Center in Cleveland on the brand-new antithrombotic therapy from the ACCP took attendees through key aspects of the new guidelines. Dr. Curley used the more controversial topics as examples: treatment of submassive PE, use of catheter-directed thrombolysis in patients with acute DVT, recommended VTE prophylaxis. She even threw in some anatomy lessons for clinicians.

SESSION

HM12 Pre-Course: Medical Procedures for the Hospitalist

Bradley Rosen, MD, MBA, FHM, of Cedars Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, Sally Wang, MD, FHM, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital’s in Boston, and Joshua Lenchus, DO, RPh, SFHM, of the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine led a motivated group of hospitalists through hands-on training in bedside invasive procedures during two half-day pre-course sessions at HM12. With emphasis on ultrasound guidance and evidence-based practices, the faculty provided the sold-out audience with lively discussions and small-group experiential education in central venous catheter placement, paracentesis, thoracentsis, lumbar puncture (LP), and other bedside procedures.

Although bedside procedures have long been a staple of internal-medicine practice, the field of procedural medicine has increasingly become the domain of hospitalists, many of whom call themselves proceduralists. Nearly all procedures can be aided by ultrasound guidance, and for many procedures, ultrasound guidance is the standard of care.

SESSION

ACCP Antithrombotic Therapy Guideline: The Questions that Remain Unanswered

Daniel Brotman, MD, FACP, FHM, of Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore addressed questions all hospitalists wonder about: Is warfarin still the best anticoagulant in atrial fibrillation (afib)?; Should DVT prevention extend beyond hospitalization?; When should anticoagulation be started in stroke patients with afib?

Warfarin, Dr. Brotman explained, has many disadvantages, and new oral anticoagulants (e.g. dabigatran, apixaban, rivaoxaban) offer many advantages with lower side-effect profiles. All of the new agents appear to have either better efficacy or trend toward better efficacy; none require monitoring, and all have lower rates of ICH.

Prices are higher for new agents but are competitive with other drugs currently on the market for other diseases. Use dabigatran with caution in patients with renal failure, and realize that there is no antidote for any of these drugs. Dabigatran is acidic and causes gastrointestinal (GI) upset, thus has a higher rate of GI bleeding. Stop any of these five days prior to planned procedures, longer if patients are at high risk of bleeding.

Evidence from RCTs in hospitalized surgical patients suggests that VTE prophylaxis should be continued in patients undergoing hip surgery and surgery for abdominal or pelvic malignancy. Patients admitted for acute medical illness do not benefit from VTE prophylaxis beyond acute hospitalization, even if immobilized, unless they have solid tumors with additional risk factors (hormone use, prior VTE, etc.) and are at low risk for bleeding. Chronically immobilized patients do not benefit from VTE prophylaxis beyond the acute hospitalization.

Oral anticoagulants can be started within one to two weeks of stroke onset. The larger the stroke, the greater the risk of hemorrhagic transformation with early anticoagulation, so the smaller the stroke, the safer it is to start early. VTE prophylaxis is important regardless.

SESSION

Update in Hospital Medicine

Facing a packed house in the main auditorium, Kevin O’Leary, MD, of Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago and Efren Manjarrez, MD, from the University of Miami’s Miller School of Medicine synthesized dozens of research articles that are clinically relevant to hospitalists everywhere. “We looked for articles that would change or modify your current practice,” Dr. O’Leary said.

SESSION

Complicated Pneumonia and Acute Hematogenous Osteomyelitis: New Insights into Diagnosis and Management

The etiologic agents for complicated pneumonias and osteomyelitis have changed recently, according to Vanderbilt University School of Medicine’s Derek Williams, MD, MPH, and C. Buddy Creech, MD, MPH, who assisted pediatric hospitalists in updated diagnosis and intervention strategies.

The increase in complicated pneumonias and empyemas is mostly due to the increase in Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype 19a. After introduction of the PCV-7 vaccine, incidence of serotype 19a infections increased to 98% of infections. Serotype 19a is now included in the PCV-13 vaccine, approved by the FDA in 2011. There are multiple interventions available for empyemas, including chest tube alone, chest tube with fibrinolysis, and VATS. Current research is being done to assess efficacy for these measures.

Osteomyelitis might be caused by direct inoculation, spread from local infection, or hematogenous spread. S. aureus is a causative agent in 80% to 90% of patients. MRSA infection has a more complicated course. Based on patient response and inflammatory markers, a short course of intravenous antibiotics followed by oral antibiotics might be appropriate.

SESSION

DVT Prophylaxis: Don’t Forget the Pediatric Patients

Most would agree that hospitalists have seen more thrombosis in children over the past decade, and although it isn’t known why, it is likely due to multifactorial causes, said Leslie Raffini, MD, MSCE, director of the Hemostasis and Thrombosis Center at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

Central venous catheters remain a significant risk factor for venous thromboembolism (VTE), and our knowledge of inherited risk factors has expanded in recent years. While it is likely that inherited risk factors increase the risk of thrombosis in children, the question of testing has engendered debate, due in large part to the lack of clear benefit of that information in the majority of situations.

“The decision to test should be made on an individual basis, after counseling,” said Dr. Raffini. “Results should be interpreted by an experienced physician with adolescent females most likely to benefit from the testing. There are no recommendations for what to do with pediatric patients” despite the fact that this is an important cause of morbidity in high-risk patients.

Dr. Raffini described efforts at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia that led to a VTE prophylaxis guideline. Successful implementation of the guideline required significant multidisciplinary collaboration, and an analysis of outcomes is under way.

SESSION

Updates from the 9th ACCP Antithrombotic Therapy Guidelines

The evidence-based, rapid-fire presentation by Catherine Curley, MD, of MetroHealth Medical Center in Cleveland on the brand-new antithrombotic therapy from the ACCP took attendees through key aspects of the new guidelines. Dr. Curley used the more controversial topics as examples: treatment of submassive PE, use of catheter-directed thrombolysis in patients with acute DVT, recommended VTE prophylaxis. She even threw in some anatomy lessons for clinicians.

SESSION

HM12 Pre-Course: Medical Procedures for the Hospitalist

Bradley Rosen, MD, MBA, FHM, of Cedars Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, Sally Wang, MD, FHM, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital’s in Boston, and Joshua Lenchus, DO, RPh, SFHM, of the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine led a motivated group of hospitalists through hands-on training in bedside invasive procedures during two half-day pre-course sessions at HM12. With emphasis on ultrasound guidance and evidence-based practices, the faculty provided the sold-out audience with lively discussions and small-group experiential education in central venous catheter placement, paracentesis, thoracentsis, lumbar puncture (LP), and other bedside procedures.

Although bedside procedures have long been a staple of internal-medicine practice, the field of procedural medicine has increasingly become the domain of hospitalists, many of whom call themselves proceduralists. Nearly all procedures can be aided by ultrasound guidance, and for many procedures, ultrasound guidance is the standard of care.

SESSION

ACCP Antithrombotic Therapy Guideline: The Questions that Remain Unanswered

Daniel Brotman, MD, FACP, FHM, of Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore addressed questions all hospitalists wonder about: Is warfarin still the best anticoagulant in atrial fibrillation (afib)?; Should DVT prevention extend beyond hospitalization?; When should anticoagulation be started in stroke patients with afib?

Warfarin, Dr. Brotman explained, has many disadvantages, and new oral anticoagulants (e.g. dabigatran, apixaban, rivaoxaban) offer many advantages with lower side-effect profiles. All of the new agents appear to have either better efficacy or trend toward better efficacy; none require monitoring, and all have lower rates of ICH.

Prices are higher for new agents but are competitive with other drugs currently on the market for other diseases. Use dabigatran with caution in patients with renal failure, and realize that there is no antidote for any of these drugs. Dabigatran is acidic and causes gastrointestinal (GI) upset, thus has a higher rate of GI bleeding. Stop any of these five days prior to planned procedures, longer if patients are at high risk of bleeding.

Evidence from RCTs in hospitalized surgical patients suggests that VTE prophylaxis should be continued in patients undergoing hip surgery and surgery for abdominal or pelvic malignancy. Patients admitted for acute medical illness do not benefit from VTE prophylaxis beyond acute hospitalization, even if immobilized, unless they have solid tumors with additional risk factors (hormone use, prior VTE, etc.) and are at low risk for bleeding. Chronically immobilized patients do not benefit from VTE prophylaxis beyond the acute hospitalization.

Oral anticoagulants can be started within one to two weeks of stroke onset. The larger the stroke, the greater the risk of hemorrhagic transformation with early anticoagulation, so the smaller the stroke, the safer it is to start early. VTE prophylaxis is important regardless.

SESSION

Update in Hospital Medicine

Facing a packed house in the main auditorium, Kevin O’Leary, MD, of Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago and Efren Manjarrez, MD, from the University of Miami’s Miller School of Medicine synthesized dozens of research articles that are clinically relevant to hospitalists everywhere. “We looked for articles that would change or modify your current practice,” Dr. O’Leary said.

SESSION

Complicated Pneumonia and Acute Hematogenous Osteomyelitis: New Insights into Diagnosis and Management

The etiologic agents for complicated pneumonias and osteomyelitis have changed recently, according to Vanderbilt University School of Medicine’s Derek Williams, MD, MPH, and C. Buddy Creech, MD, MPH, who assisted pediatric hospitalists in updated diagnosis and intervention strategies.

The increase in complicated pneumonias and empyemas is mostly due to the increase in Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype 19a. After introduction of the PCV-7 vaccine, incidence of serotype 19a infections increased to 98% of infections. Serotype 19a is now included in the PCV-13 vaccine, approved by the FDA in 2011. There are multiple interventions available for empyemas, including chest tube alone, chest tube with fibrinolysis, and VATS. Current research is being done to assess efficacy for these measures.

Osteomyelitis might be caused by direct inoculation, spread from local infection, or hematogenous spread. S. aureus is a causative agent in 80% to 90% of patients. MRSA infection has a more complicated course. Based on patient response and inflammatory markers, a short course of intravenous antibiotics followed by oral antibiotics might be appropriate.

SESSION

DVT Prophylaxis: Don’t Forget the Pediatric Patients

Most would agree that hospitalists have seen more thrombosis in children over the past decade, and although it isn’t known why, it is likely due to multifactorial causes, said Leslie Raffini, MD, MSCE, director of the Hemostasis and Thrombosis Center at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

Central venous catheters remain a significant risk factor for venous thromboembolism (VTE), and our knowledge of inherited risk factors has expanded in recent years. While it is likely that inherited risk factors increase the risk of thrombosis in children, the question of testing has engendered debate, due in large part to the lack of clear benefit of that information in the majority of situations.

“The decision to test should be made on an individual basis, after counseling,” said Dr. Raffini. “Results should be interpreted by an experienced physician with adolescent females most likely to benefit from the testing. There are no recommendations for what to do with pediatric patients” despite the fact that this is an important cause of morbidity in high-risk patients.

Dr. Raffini described efforts at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia that led to a VTE prophylaxis guideline. Successful implementation of the guideline required significant multidisciplinary collaboration, and an analysis of outcomes is under way.

SESSION

Updates from the 9th ACCP Antithrombotic Therapy Guidelines

The evidence-based, rapid-fire presentation by Catherine Curley, MD, of MetroHealth Medical Center in Cleveland on the brand-new antithrombotic therapy from the ACCP took attendees through key aspects of the new guidelines. Dr. Curley used the more controversial topics as examples: treatment of submassive PE, use of catheter-directed thrombolysis in patients with acute DVT, recommended VTE prophylaxis. She even threw in some anatomy lessons for clinicians.

SESSION

HM12 Pre-Course: Medical Procedures for the Hospitalist

Bradley Rosen, MD, MBA, FHM, of Cedars Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, Sally Wang, MD, FHM, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital’s in Boston, and Joshua Lenchus, DO, RPh, SFHM, of the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine led a motivated group of hospitalists through hands-on training in bedside invasive procedures during two half-day pre-course sessions at HM12. With emphasis on ultrasound guidance and evidence-based practices, the faculty provided the sold-out audience with lively discussions and small-group experiential education in central venous catheter placement, paracentesis, thoracentsis, lumbar puncture (LP), and other bedside procedures.

Although bedside procedures have long been a staple of internal-medicine practice, the field of procedural medicine has increasingly become the domain of hospitalists, many of whom call themselves proceduralists. Nearly all procedures can be aided by ultrasound guidance, and for many procedures, ultrasound guidance is the standard of care.

SESSION

ACCP Antithrombotic Therapy Guideline: The Questions that Remain Unanswered

Daniel Brotman, MD, FACP, FHM, of Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore addressed questions all hospitalists wonder about: Is warfarin still the best anticoagulant in atrial fibrillation (afib)?; Should DVT prevention extend beyond hospitalization?; When should anticoagulation be started in stroke patients with afib?

Warfarin, Dr. Brotman explained, has many disadvantages, and new oral anticoagulants (e.g. dabigatran, apixaban, rivaoxaban) offer many advantages with lower side-effect profiles. All of the new agents appear to have either better efficacy or trend toward better efficacy; none require monitoring, and all have lower rates of ICH.

Prices are higher for new agents but are competitive with other drugs currently on the market for other diseases. Use dabigatran with caution in patients with renal failure, and realize that there is no antidote for any of these drugs. Dabigatran is acidic and causes gastrointestinal (GI) upset, thus has a higher rate of GI bleeding. Stop any of these five days prior to planned procedures, longer if patients are at high risk of bleeding.

Evidence from RCTs in hospitalized surgical patients suggests that VTE prophylaxis should be continued in patients undergoing hip surgery and surgery for abdominal or pelvic malignancy. Patients admitted for acute medical illness do not benefit from VTE prophylaxis beyond acute hospitalization, even if immobilized, unless they have solid tumors with additional risk factors (hormone use, prior VTE, etc.) and are at low risk for bleeding. Chronically immobilized patients do not benefit from VTE prophylaxis beyond the acute hospitalization.

Oral anticoagulants can be started within one to two weeks of stroke onset. The larger the stroke, the greater the risk of hemorrhagic transformation with early anticoagulation, so the smaller the stroke, the safer it is to start early. VTE prophylaxis is important regardless.

SESSION

Update in Hospital Medicine

Facing a packed house in the main auditorium, Kevin O’Leary, MD, of Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago and Efren Manjarrez, MD, from the University of Miami’s Miller School of Medicine synthesized dozens of research articles that are clinically relevant to hospitalists everywhere. “We looked for articles that would change or modify your current practice,” Dr. O’Leary said.

SESSION

Complicated Pneumonia and Acute Hematogenous Osteomyelitis: New Insights into Diagnosis and Management

The etiologic agents for complicated pneumonias and osteomyelitis have changed recently, according to Vanderbilt University School of Medicine’s Derek Williams, MD, MPH, and C. Buddy Creech, MD, MPH, who assisted pediatric hospitalists in updated diagnosis and intervention strategies.

The increase in complicated pneumonias and empyemas is mostly due to the increase in Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype 19a. After introduction of the PCV-7 vaccine, incidence of serotype 19a infections increased to 98% of infections. Serotype 19a is now included in the PCV-13 vaccine, approved by the FDA in 2011. There are multiple interventions available for empyemas, including chest tube alone, chest tube with fibrinolysis, and VATS. Current research is being done to assess efficacy for these measures.

Osteomyelitis might be caused by direct inoculation, spread from local infection, or hematogenous spread. S. aureus is a causative agent in 80% to 90% of patients. MRSA infection has a more complicated course. Based on patient response and inflammatory markers, a short course of intravenous antibiotics followed by oral antibiotics might be appropriate.

HM12 Pre-Course Session Emphasizes Ultrasound-Guidance, Evidence-Based Practices

Summation

While bedside procedures have been long been a staple of internal medicine practice, the field of procedural medicine has increasingly become the dominion of hospitalists and now proceduralists. Nearly all procedures now can be aided by ultrasound guidance, and for many procedures, ultrasound guidance is standard of care.

“You think you’re a pretty good driver, but you wouldn’t drive down the road with your headlights off,” said Mark Ault, MD, director of the division of general internal medicine at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles. “On your flight home, I’m sure you wouldn’t want your pilot flying with his controls off.”

Takeaways

• Performing bedside procedures safely requires specific training and steady experience that is well-suited to healthcare providers in hospital medicine.

• Ultrasound guidance is considered standard of care for central venous catheter placement, paracentesis, and thoracentesis.

• Widely accepted limitations in fluid removal thought to prevent re-expansion pulmonary edema (RPE) after thoracentesis may not prove to be valid.

• Arbitrary cutoffs for INR and platelet count in paracentesis are based on data that may not be valid in bedside paracentesis.

• Use of non-traumatic lumbar puncture needles, such as the Gertie-Marx and Sprotte needles, may reduce the incidence of post-LP headache.

• Fine-needle aspiration, punch skin biopsy, and arthrocentesis are bedside procedures that can be mastered by hospitalists and used regularly in their practice.

• Establishing a proceduralist group or center initially requires showing to hospital administrators benefits other than revenue, such as reduction in CLABSI and off-loading other procedural services.

Dr. Chang is a pediatric hospitalist at the University of San Diego Medical Center and Rady Children's Hospital in San Diego, Calif.

Summation

While bedside procedures have been long been a staple of internal medicine practice, the field of procedural medicine has increasingly become the dominion of hospitalists and now proceduralists. Nearly all procedures now can be aided by ultrasound guidance, and for many procedures, ultrasound guidance is standard of care.

“You think you’re a pretty good driver, but you wouldn’t drive down the road with your headlights off,” said Mark Ault, MD, director of the division of general internal medicine at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles. “On your flight home, I’m sure you wouldn’t want your pilot flying with his controls off.”

Takeaways

• Performing bedside procedures safely requires specific training and steady experience that is well-suited to healthcare providers in hospital medicine.

• Ultrasound guidance is considered standard of care for central venous catheter placement, paracentesis, and thoracentesis.

• Widely accepted limitations in fluid removal thought to prevent re-expansion pulmonary edema (RPE) after thoracentesis may not prove to be valid.

• Arbitrary cutoffs for INR and platelet count in paracentesis are based on data that may not be valid in bedside paracentesis.

• Use of non-traumatic lumbar puncture needles, such as the Gertie-Marx and Sprotte needles, may reduce the incidence of post-LP headache.

• Fine-needle aspiration, punch skin biopsy, and arthrocentesis are bedside procedures that can be mastered by hospitalists and used regularly in their practice.

• Establishing a proceduralist group or center initially requires showing to hospital administrators benefits other than revenue, such as reduction in CLABSI and off-loading other procedural services.

Dr. Chang is a pediatric hospitalist at the University of San Diego Medical Center and Rady Children's Hospital in San Diego, Calif.

Summation

While bedside procedures have been long been a staple of internal medicine practice, the field of procedural medicine has increasingly become the dominion of hospitalists and now proceduralists. Nearly all procedures now can be aided by ultrasound guidance, and for many procedures, ultrasound guidance is standard of care.

“You think you’re a pretty good driver, but you wouldn’t drive down the road with your headlights off,” said Mark Ault, MD, director of the division of general internal medicine at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles. “On your flight home, I’m sure you wouldn’t want your pilot flying with his controls off.”

Takeaways

• Performing bedside procedures safely requires specific training and steady experience that is well-suited to healthcare providers in hospital medicine.

• Ultrasound guidance is considered standard of care for central venous catheter placement, paracentesis, and thoracentesis.

• Widely accepted limitations in fluid removal thought to prevent re-expansion pulmonary edema (RPE) after thoracentesis may not prove to be valid.

• Arbitrary cutoffs for INR and platelet count in paracentesis are based on data that may not be valid in bedside paracentesis.

• Use of non-traumatic lumbar puncture needles, such as the Gertie-Marx and Sprotte needles, may reduce the incidence of post-LP headache.

• Fine-needle aspiration, punch skin biopsy, and arthrocentesis are bedside procedures that can be mastered by hospitalists and used regularly in their practice.

• Establishing a proceduralist group or center initially requires showing to hospital administrators benefits other than revenue, such as reduction in CLABSI and off-loading other procedural services.

Dr. Chang is a pediatric hospitalist at the University of San Diego Medical Center and Rady Children's Hospital in San Diego, Calif.

Transitioning Pediatric Patients with Chronic Conditions

Last September, Seattle Children’s Hospital hosted a “graduation day” party for one of its longtime patients, Robyn Nichols.

Robyn first entered the hospital as a 21-month-old after a major car accident that left her a quadriplegic and ventilator-dependent. She was in a coma for nine weeks and spent many days and nights in the children’s hospital. Now 20 years old, she’s ready to be cared for in an adult hospital when the need arises.

Her mother, Amy Thompson, wrote a letter thanking the staff for their dedication. And while she’s sad to say goodbye, she’s grateful for their efforts in overseeing the shift in Robyn’s care to adult specialists.

“If I were to let a doctor know one thing about transitioning a pediatric [patient] to adult care, [it] is for them to recognize how scary it is for the patient as well as the family,” Thompson says. “After being in the adult world with a special-needs adult daughter for a couple of months, I want to go back [to the children’s hospital]. The unknown, when you are talking life and death, can be terrorizing.”

As pediatric patients with chronic medical conditions enter adolescence and the young adult years, proper transitions can make a significant difference in their inpatient and outpatient care. And with thoughtful collaboration, hospitalists can deliver solutions that lead to good outcomes.

“A safe transition provides a great deal of relief and comfort to the families of these patients,” says Moises Auron, MD, FAAP, FACP, assistant professor of medicine and pediatrics at The Cleveland Clinic.

Delayed Dangers

Anticipating a maturing adolescent’s care needs is paramount. Chronic diseases diagnosed in childhood often lead to complications in the teen years and early adulthood. Over time, more complex treatments might be necessary. For instance, Dr. Auron says, a patient living with diabetes since age 5 could require a kidney transplant at age 25.

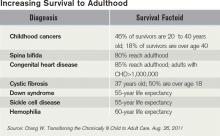

Childhood cancer survivors also tend to encounter major health challenges as adults, according to an Oct. 13, 2011, report in the New England Journal of Medicine. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is the most common pediatric cancer, with a cure rate surpassing 70%. However, adult survivors of childhood leukemia have heightened risks of secondary cancers, cardiovascular disease, and other chronic illnesses.1

Assembling transitions-of-care teams is one way that hospitals can help coordinate services for such patients. As these patients mature and “quit seeing their pediatrician, they don’t usually see anybody,” says W. Benjamin Rothwell, MD, associate director of the “med-peds” residency at Tulane University School of Medicine in New Orleans. “At that point, they kind of fall off the map, so to speak, until they present to the hospital acutely ill.”

New Orleans has a large population of pediatric patients with sickle-cell anemia, a genetic disease that is more prevalent in blacks. Dr. Rothwell says he and his colleagues strive to transition these patients between the ages of 16 and 26. “The goal,” he says, “is to try to catch people in that 10-year span.”

Other conditions that add to the complexity of care for hospitalists include cerebral palsy, chromosomal abnormalities, congenital heart disease, and pregnancy in teenagers with chronic illnesses. Adult hospitalists might not be fully prepared to deal with developmentally disabled patients.

In such cases, “the family member or caregiver is a trusted ally in knowing what’s going on,” says Susan Hunt, MD, a hospitalist at Seattle Children’s Hospital and University of Washington Medical Center. “It may not be typical for adult providers to expect that kind of communication.” When put into this situation, hospitalists can enlist the caregiver’s input—for instance, asking, “How does your child show pain?”

When patients rely on medical devices, such as a gastric feeding tube, tracheotomy, or wheelchair, it helps to know where the family or previous facility obtained the specific equipment in case a replacement becomes necessary. Staying on top of the patient’s insurance coverage also is vital in a transition, Dr. Hunt says.

Communication should flow easily between providers in inpatient and outpatient settings, as adolescents with chronic conditions are “aging out of the pediatric system,” says Allen Friedland, MD, program director of the combined med-peds residency at Christiana Care Health System in Newark, Del.

Soon they are “thrust into the adult world, which has an entirely different paradigm,” Dr. Friedland says. Among the challenges is linking a hospital’s electronic health records to interface with the information given to the outpatient physicians overseeing a patient’s care.

Christiana Care Health System has collaborated with Nemours/Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children in nearby Wilmington, Del., to transition patients with complex medical conditions into adult care. Nemours is providing comprehensive summaries, which indicate the types of subspecialty care that a patient could require in the future. “We sort of take some of the mystery out,” Dr. Friedland says. “We really anticipate the issues.”

—Emily Chapman, MD, pediatric hospitalist, Children’s Hospitals & Clinics of Minnesota, Minneapolis

Meanwhile, Christiana Care started an outpatient primary-care practice staffed by two physicians, a social worker, and a psychologist liaison. They coordinate with a physician and social worker at Nemours. Secure email also helps facilitate discussions about transitions of care between the pediatric and adult settings.

The teams have access to the transition-care practice providers for round-the-clock consultations, and Dr. Friedland assists in admitting patients to the most appropriate level of hospitalized care. “When a person goes to the ED,” he explains, “there’s already a set of expectations and orders.”

The Choice Is Yours

When staying in the hospital, some patients feel more comfortable on a pediatric floor, others in an adult environment. That’s why Keely Dwyer-Matzky, MD, and Amy Blatt, MD, both Med-Peds hospitalists, created an educational video for adolescent patients at the University of Rochester Medical Center in New York.

“There’s a lot of fear about transitioning, not knowing what it’s going to be like, what the expectations are, or the feeling of the floor itself,” Dr. Dwyer-Matzky says. The video informs viewers about the importance of keeping medical summaries of their problems and speaking up for themselves at visits to their doctors’ offices. It also mentions that the Rochester facility gives adolescents the option to tour an adult floor.

“There are a lot of variables,” says Shelley W. Collins, MD, chief of the pediatric hospitalist division at the University of Florida at Gainesville. “If their cognitive level allows them to be participants in their own care, then I think we have obligation to ask them what their preference is.”

The state law that governs where an HM group practices also factors into the equation. In an emergency, a court order could be obtained if a procedure is deemed necessary and a legal guardian has not been established or the patient will not consent, Dr. Collins says of Florida law. “But we prefer to have a patient agree to it. In fact, we like and require the assent of a teenage patient, who can give it in addition to the consent of the parents.”

Dr. Collins and her colleague Arwa Saidi, MD, a pediatric cardiologist, propose “a transition checklist” for hospitalists to review and update every time a pediatric or adolescent patient with a chronic condition arrives at the hospital. This aggregate of information becomes part of the medical record for hospitalists to consult in the future.

Adolescents can present with adult-related problems such as heart disease or stroke. These are the sorts of issues that pediatric hospitalist may not be as comfortable handling. Meanwhile, adult hospitalists encounter child-related issues that don’t normally enter their territory.

For instance, with a patient admitted to the hospital for an asthma flare or diabetic ketoacidosis, adult hospitalists might be unaware of school rules pertaining to inhalers and insulin injections, says Weijen Chang, MD, FAAP, FACP, a hospitalist experienced in treating both adult and pediatric patients at the University of California at San Diego (UCSD).

“They’re not used to interacting with school systems in regards to someone’s health care,” says Dr. Chang, a Team Hospitalist member. “The best solution, as always, is education.”

—Amy Thompson, parent

In April, hospitalists trained in both internal medicine and pediatrics will convene at SHM’s annual meeting in San Diego to educate their peers in managing difficult and unfamiliar situations. (The April 4 workshop, “Demystifying Medical Care of Adults with Chronic Diseases of Childhood: What the Hospitalist Should Know,” has limited seating; visit www.hospitalmedicine2012.org to register.)

At UCSD-affiliated Rady Children’s Hospital, hospitalists encountered a patient who was very agitated and combative toward staff. That wasn’t so unusual, except that the patient was quite large in size. “They were uncomfortable with the physical nature of the interaction,” Dr. Chang says.

The physicians and nurses on a pediatric floor also might not be comfortable with obstetrics, and they might lack the equipment for monitoring fetal heart tones and other vitals. In this case, a pregnant teen would be best served in an adult hospital. On the flip side, an adult hospital might not have a blood pressure cuff small enough for some adolescent patients, says Heather Toth, MD, program director of the med-peds residency at the Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee. Collaboration between adult and pediatric providers is essential in ironing out these types of kinks.