User login

Tools emerging to predict liver failure in cirrhosis

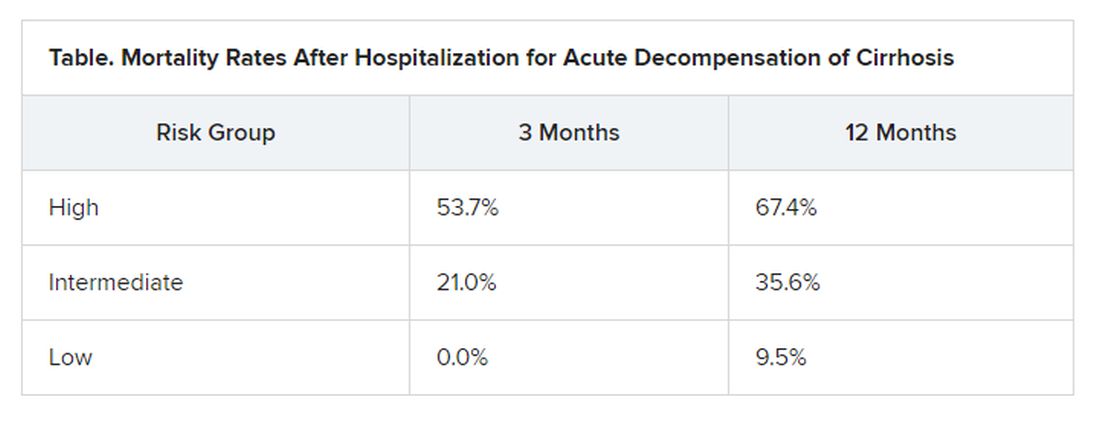

Systemic inflammation and portal hypertension are key predictors of acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) in the 3 months after a hospital stay for acute decompensated cirrhosis and also of death after 12 months, a preliminary analysis of data from the PREDICT study shows.

“Before this, we never had any patient signatures to identify ACLF,” said Jonel Trebicka, MD, PhD, from the JW Goethe University Hospital in Frankfurt, Germany.

Now, Dr. Trebicka’s team has “characterized the phenotypes in pre-ACLF that will progress within 3 months,” he said in an interview. “Those with high levels of inflammatory proteins, white blood cell count, are more likely to develop ACLF.”

ACLF is a highly complex disorder that can lead liver, cardiovascular, renal, cerebral, pulmonary, intestinal, adrenal, and immune systems to fail, Dr. Trebicka explained when he discussed the analysis – published online in the Journal of Hepatology – during the virtual International Liver Congress (ILC) 2020.

The chance of survival after the onset of ACLF is low – the 28-day survival rate is 30% – and “the only treatment we have is liver transplant,” he said.

For their prospective observational study, Dr. Trebicka and his colleagues assessed 1071 participants from 48 European hospitals in 14 countries who were admitted for an episode of acute decompensation, defined as the development of ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, infection, or a combination thereof.

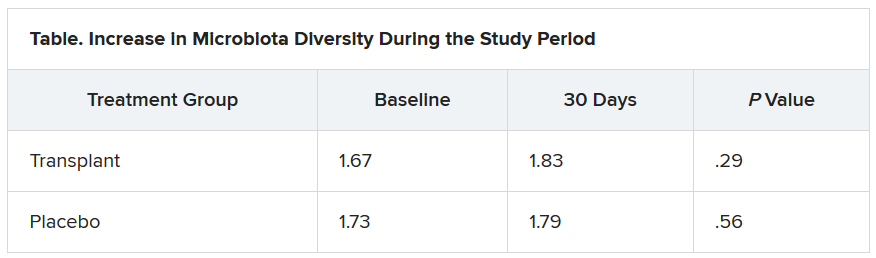

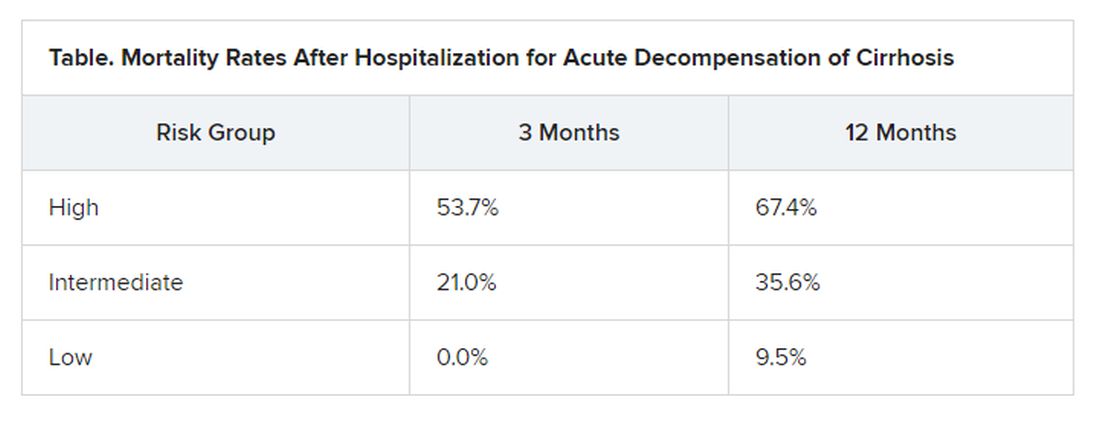

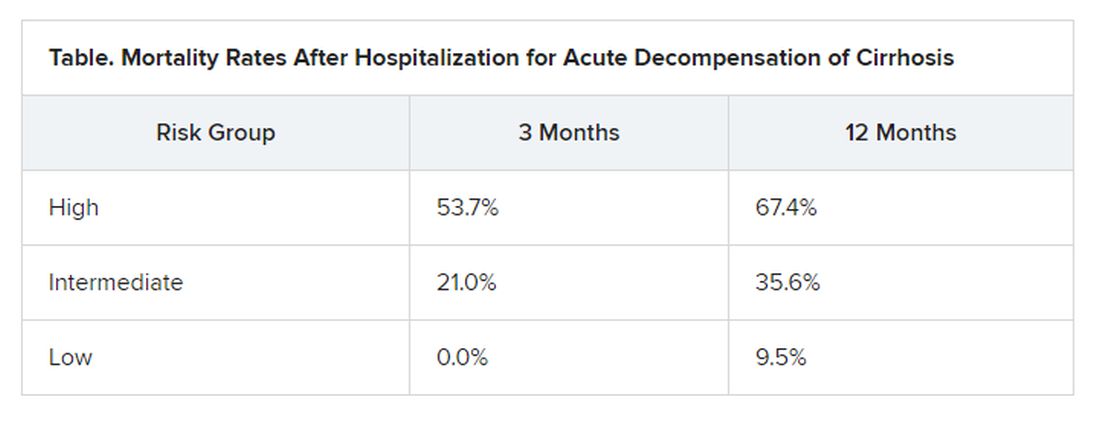

The researchers identified three distinct clinical courses for a patient hospitalized with acute decompensated cirrhosis that will help clinicians predict the development of ACLF.

At study enrollment, more than half of the patients at highest risk for ACLF had pre-ACLF and high-grade systemic inflammation. The patients at intermediate risk had unstable decompensated cirrhosis with low-grade systemic inflammation and complications related to severe portal hypertension. And those at lowest risk for ACLF had stable decompensated cirrhosis and no severe systemic inflammation or portal hypertension complications, and did not develop ACLF or another episode of acute decompensation in the subsequent 3 months.

“There have been hints of possible phenotypes before – for stable and unstable ACLF – but we never had anything specific to diagnose,” Trebicka reported.

“We found that there are two main mechanisms in the development of ACLF that are most important,” he said. The first is systemic inflammation with high levels of proteins, which “leads to organ failure. This is the most striking acute mechanism.”

The second is the development of portal hypertension. “This is slower, but also very important, causing increased pressure in the portal vein, and leading to bleeding if the pressure is too great,” he said.

More tools emerging to help predict ACLF

The Albumin-functionality-test (AFT), which uses serum albumin levels to evaluate liver and kidney function, might also be useful in the prediction of ACLF and 12-month survival, according to a separate study an Italian group presented at the virtual ILC.

“Our main results are that parameters from albumin predict the development of ACLF in acute decompensated patients with the same diagnostic performance as the CLIF-AD score,” said Katja Waterstradt, PhD, from the University of Bologna in Italy.

And when the two tests are combined, diagnostic performance is increased, she added.

Dr. Trebicka has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Waterstrand is a researcher for MedInnovation GmbH.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Systemic inflammation and portal hypertension are key predictors of acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) in the 3 months after a hospital stay for acute decompensated cirrhosis and also of death after 12 months, a preliminary analysis of data from the PREDICT study shows.

“Before this, we never had any patient signatures to identify ACLF,” said Jonel Trebicka, MD, PhD, from the JW Goethe University Hospital in Frankfurt, Germany.

Now, Dr. Trebicka’s team has “characterized the phenotypes in pre-ACLF that will progress within 3 months,” he said in an interview. “Those with high levels of inflammatory proteins, white blood cell count, are more likely to develop ACLF.”

ACLF is a highly complex disorder that can lead liver, cardiovascular, renal, cerebral, pulmonary, intestinal, adrenal, and immune systems to fail, Dr. Trebicka explained when he discussed the analysis – published online in the Journal of Hepatology – during the virtual International Liver Congress (ILC) 2020.

The chance of survival after the onset of ACLF is low – the 28-day survival rate is 30% – and “the only treatment we have is liver transplant,” he said.

For their prospective observational study, Dr. Trebicka and his colleagues assessed 1071 participants from 48 European hospitals in 14 countries who were admitted for an episode of acute decompensation, defined as the development of ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, infection, or a combination thereof.

The researchers identified three distinct clinical courses for a patient hospitalized with acute decompensated cirrhosis that will help clinicians predict the development of ACLF.

At study enrollment, more than half of the patients at highest risk for ACLF had pre-ACLF and high-grade systemic inflammation. The patients at intermediate risk had unstable decompensated cirrhosis with low-grade systemic inflammation and complications related to severe portal hypertension. And those at lowest risk for ACLF had stable decompensated cirrhosis and no severe systemic inflammation or portal hypertension complications, and did not develop ACLF or another episode of acute decompensation in the subsequent 3 months.

“There have been hints of possible phenotypes before – for stable and unstable ACLF – but we never had anything specific to diagnose,” Trebicka reported.

“We found that there are two main mechanisms in the development of ACLF that are most important,” he said. The first is systemic inflammation with high levels of proteins, which “leads to organ failure. This is the most striking acute mechanism.”

The second is the development of portal hypertension. “This is slower, but also very important, causing increased pressure in the portal vein, and leading to bleeding if the pressure is too great,” he said.

More tools emerging to help predict ACLF

The Albumin-functionality-test (AFT), which uses serum albumin levels to evaluate liver and kidney function, might also be useful in the prediction of ACLF and 12-month survival, according to a separate study an Italian group presented at the virtual ILC.

“Our main results are that parameters from albumin predict the development of ACLF in acute decompensated patients with the same diagnostic performance as the CLIF-AD score,” said Katja Waterstradt, PhD, from the University of Bologna in Italy.

And when the two tests are combined, diagnostic performance is increased, she added.

Dr. Trebicka has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Waterstrand is a researcher for MedInnovation GmbH.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Systemic inflammation and portal hypertension are key predictors of acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) in the 3 months after a hospital stay for acute decompensated cirrhosis and also of death after 12 months, a preliminary analysis of data from the PREDICT study shows.

“Before this, we never had any patient signatures to identify ACLF,” said Jonel Trebicka, MD, PhD, from the JW Goethe University Hospital in Frankfurt, Germany.

Now, Dr. Trebicka’s team has “characterized the phenotypes in pre-ACLF that will progress within 3 months,” he said in an interview. “Those with high levels of inflammatory proteins, white blood cell count, are more likely to develop ACLF.”

ACLF is a highly complex disorder that can lead liver, cardiovascular, renal, cerebral, pulmonary, intestinal, adrenal, and immune systems to fail, Dr. Trebicka explained when he discussed the analysis – published online in the Journal of Hepatology – during the virtual International Liver Congress (ILC) 2020.

The chance of survival after the onset of ACLF is low – the 28-day survival rate is 30% – and “the only treatment we have is liver transplant,” he said.

For their prospective observational study, Dr. Trebicka and his colleagues assessed 1071 participants from 48 European hospitals in 14 countries who were admitted for an episode of acute decompensation, defined as the development of ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, infection, or a combination thereof.

The researchers identified three distinct clinical courses for a patient hospitalized with acute decompensated cirrhosis that will help clinicians predict the development of ACLF.

At study enrollment, more than half of the patients at highest risk for ACLF had pre-ACLF and high-grade systemic inflammation. The patients at intermediate risk had unstable decompensated cirrhosis with low-grade systemic inflammation and complications related to severe portal hypertension. And those at lowest risk for ACLF had stable decompensated cirrhosis and no severe systemic inflammation or portal hypertension complications, and did not develop ACLF or another episode of acute decompensation in the subsequent 3 months.

“There have been hints of possible phenotypes before – for stable and unstable ACLF – but we never had anything specific to diagnose,” Trebicka reported.

“We found that there are two main mechanisms in the development of ACLF that are most important,” he said. The first is systemic inflammation with high levels of proteins, which “leads to organ failure. This is the most striking acute mechanism.”

The second is the development of portal hypertension. “This is slower, but also very important, causing increased pressure in the portal vein, and leading to bleeding if the pressure is too great,” he said.

More tools emerging to help predict ACLF

The Albumin-functionality-test (AFT), which uses serum albumin levels to evaluate liver and kidney function, might also be useful in the prediction of ACLF and 12-month survival, according to a separate study an Italian group presented at the virtual ILC.

“Our main results are that parameters from albumin predict the development of ACLF in acute decompensated patients with the same diagnostic performance as the CLIF-AD score,” said Katja Waterstradt, PhD, from the University of Bologna in Italy.

And when the two tests are combined, diagnostic performance is increased, she added.

Dr. Trebicka has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Waterstrand is a researcher for MedInnovation GmbH.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Many advanced countries missing targets for HCV elimination

Eleven high-income countries are on track to meet World Health Organization targets to eliminate hepatitis C infection by 2030, compared with 9 countries 2 years ago, researchers reported. But 28 countries, including the United States, are not expected to eliminate HCV until 2050.

“In the countries making progress, the common elements are political will, a clear national plan, and easing of restrictions on the cascade of care and testing,” Yuri Sanchez Gonzalez, PhD, director of health economics and outcomes research for biopharmaceutical company AbbVie said in an interview. That would include offering hepatitis C treatment to individuals who have liver fibrosis and those struggling with sobriety, he said. “We can’t overstate how much this is a massive driver of the hepatitis C epidemic.”

His research, presented at the digital edition of the International Liver Congress this week, showed more countries on target than in a study published 2 years ago in Liver International . “But it’s not enough,” Dr. Sanchez Gonzalez said. “We know that more than 80% of infections are in people who inject drugs. Stigmatization of drug use is still a very major issue.” Despite data clearly showing that countries who have harm-reduction programs make progress, “in many countries these programs are still illegal.”

To evaluate which countries are on target to eliminate hepatitis C by 2030, researchers performed Markov disease progression models of HCV infection in 45 high-income countries. The results showed that Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Iceland, Italy, Japan, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom are “in the green” (on target for 2030).

Austria, Malta, the Netherlands, New Zealand, and South Korea are “in the yellow” (on target for 2040), and 28 remaining countries, including the United States, are “in the red,” with targets estimated to be met by 2050.

Compared with an analysis performed 2 years ago, South Korea moved from green to yellow, while Canada, Germany, and Sweden moved from red to green.

Researchers say that the countries moving the needle are the ones addressing barriers to care.

EASL: Eliminate barriers to treatment

During this week’s Congress, the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) launched a policy statement recommending breaking down all barriers that prevent people who inject drugs from getting access to hepatitis C treatment, including encouragement of laws and policies that “decriminalize drug use, drug possession and drug users themselves,” said statement coauthor Mojca Maticic, MD, PhD, University of Ljubljana, Slovenia.

“To reach the desired WHO goal, combining decriminalization of personal drug consumption and integrated interventions that include hepatitis C testing and treatment should be implemented,” she added. We need to adopt “an approach based on public health promotion, respect for human rights, and evidence.”

Although harm reduction is the top strategy for making 2030 targets, having precision data also helps a lot.

“High-quality data and harm-reduction innovation to curb the overdose crisis has moved us out of the red and into the green,” Canadian researcher Jordan Feld, MD, MPH, University of Toronto, said in an interview. He points to British Columbia, Canada’s third-most populous province, putting harm reduction programs in place as key to Canadian progress.

“Given the increasing opioid epidemic, you’re creating yourself a bigger problem if you don’t treat this population,” Dr. Feld said. When a person needs 6 months to get sober in order to be treated for HCV, that’s more potential time to pass the infection to others. His study, also presented at ILC this week, outlines anticipated timing of hepatitis C in Canada’s four most populous provinces (Ontario, Quebec, British Columbia, and Alberta), and shows British Columbia will reach targets by 2028.

Lifting all restrictions clearly helps, Dr. Sanchez Gonzalez reported. He pointed to Sweden as a good example, a country that recently lifted HCV treatment restrictions for individuals living with fibrosis. Sweden moved from a red to a green spot in this analysis and is now on target for 2030.

“As long as everyone who needs treatment gets treatment, you can make tremendous progress,” he said.

Keeping track is also essential to moving the needle. Since the WHO has no enforcement power, “these studies, which offer a report card of progress, really matter,” Dr. Sanchez Gonzalez explained. When a country knows where they stand, they are more likely to take action to change. “Nobody likes to be shown in the red.”

Still, “it’s not a shaming exercise,” he said. It’s about starting a conversation, showing who’s on track, and sharing how to get on track. “Knowing that there is something in your power to move the needle toward elimination by learning from your neighbors is powerful – often, it just takes political will.”

Dr. Feld has received consulting fees from AbbVie. Dr. Sanchez Gonzalez is on staff as the Director of Economics at AbbVie. Dr. Maticic has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Help your patients better understand the risks and treatment for hepatitis C by sharing AGA GI Patient Center education at http://ow.ly/xV2S30r8L29.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Eleven high-income countries are on track to meet World Health Organization targets to eliminate hepatitis C infection by 2030, compared with 9 countries 2 years ago, researchers reported. But 28 countries, including the United States, are not expected to eliminate HCV until 2050.

“In the countries making progress, the common elements are political will, a clear national plan, and easing of restrictions on the cascade of care and testing,” Yuri Sanchez Gonzalez, PhD, director of health economics and outcomes research for biopharmaceutical company AbbVie said in an interview. That would include offering hepatitis C treatment to individuals who have liver fibrosis and those struggling with sobriety, he said. “We can’t overstate how much this is a massive driver of the hepatitis C epidemic.”

His research, presented at the digital edition of the International Liver Congress this week, showed more countries on target than in a study published 2 years ago in Liver International . “But it’s not enough,” Dr. Sanchez Gonzalez said. “We know that more than 80% of infections are in people who inject drugs. Stigmatization of drug use is still a very major issue.” Despite data clearly showing that countries who have harm-reduction programs make progress, “in many countries these programs are still illegal.”

To evaluate which countries are on target to eliminate hepatitis C by 2030, researchers performed Markov disease progression models of HCV infection in 45 high-income countries. The results showed that Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Iceland, Italy, Japan, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom are “in the green” (on target for 2030).

Austria, Malta, the Netherlands, New Zealand, and South Korea are “in the yellow” (on target for 2040), and 28 remaining countries, including the United States, are “in the red,” with targets estimated to be met by 2050.

Compared with an analysis performed 2 years ago, South Korea moved from green to yellow, while Canada, Germany, and Sweden moved from red to green.

Researchers say that the countries moving the needle are the ones addressing barriers to care.

EASL: Eliminate barriers to treatment

During this week’s Congress, the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) launched a policy statement recommending breaking down all barriers that prevent people who inject drugs from getting access to hepatitis C treatment, including encouragement of laws and policies that “decriminalize drug use, drug possession and drug users themselves,” said statement coauthor Mojca Maticic, MD, PhD, University of Ljubljana, Slovenia.

“To reach the desired WHO goal, combining decriminalization of personal drug consumption and integrated interventions that include hepatitis C testing and treatment should be implemented,” she added. We need to adopt “an approach based on public health promotion, respect for human rights, and evidence.”

Although harm reduction is the top strategy for making 2030 targets, having precision data also helps a lot.

“High-quality data and harm-reduction innovation to curb the overdose crisis has moved us out of the red and into the green,” Canadian researcher Jordan Feld, MD, MPH, University of Toronto, said in an interview. He points to British Columbia, Canada’s third-most populous province, putting harm reduction programs in place as key to Canadian progress.

“Given the increasing opioid epidemic, you’re creating yourself a bigger problem if you don’t treat this population,” Dr. Feld said. When a person needs 6 months to get sober in order to be treated for HCV, that’s more potential time to pass the infection to others. His study, also presented at ILC this week, outlines anticipated timing of hepatitis C in Canada’s four most populous provinces (Ontario, Quebec, British Columbia, and Alberta), and shows British Columbia will reach targets by 2028.

Lifting all restrictions clearly helps, Dr. Sanchez Gonzalez reported. He pointed to Sweden as a good example, a country that recently lifted HCV treatment restrictions for individuals living with fibrosis. Sweden moved from a red to a green spot in this analysis and is now on target for 2030.

“As long as everyone who needs treatment gets treatment, you can make tremendous progress,” he said.

Keeping track is also essential to moving the needle. Since the WHO has no enforcement power, “these studies, which offer a report card of progress, really matter,” Dr. Sanchez Gonzalez explained. When a country knows where they stand, they are more likely to take action to change. “Nobody likes to be shown in the red.”

Still, “it’s not a shaming exercise,” he said. It’s about starting a conversation, showing who’s on track, and sharing how to get on track. “Knowing that there is something in your power to move the needle toward elimination by learning from your neighbors is powerful – often, it just takes political will.”

Dr. Feld has received consulting fees from AbbVie. Dr. Sanchez Gonzalez is on staff as the Director of Economics at AbbVie. Dr. Maticic has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Help your patients better understand the risks and treatment for hepatitis C by sharing AGA GI Patient Center education at http://ow.ly/xV2S30r8L29.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Eleven high-income countries are on track to meet World Health Organization targets to eliminate hepatitis C infection by 2030, compared with 9 countries 2 years ago, researchers reported. But 28 countries, including the United States, are not expected to eliminate HCV until 2050.

“In the countries making progress, the common elements are political will, a clear national plan, and easing of restrictions on the cascade of care and testing,” Yuri Sanchez Gonzalez, PhD, director of health economics and outcomes research for biopharmaceutical company AbbVie said in an interview. That would include offering hepatitis C treatment to individuals who have liver fibrosis and those struggling with sobriety, he said. “We can’t overstate how much this is a massive driver of the hepatitis C epidemic.”

His research, presented at the digital edition of the International Liver Congress this week, showed more countries on target than in a study published 2 years ago in Liver International . “But it’s not enough,” Dr. Sanchez Gonzalez said. “We know that more than 80% of infections are in people who inject drugs. Stigmatization of drug use is still a very major issue.” Despite data clearly showing that countries who have harm-reduction programs make progress, “in many countries these programs are still illegal.”

To evaluate which countries are on target to eliminate hepatitis C by 2030, researchers performed Markov disease progression models of HCV infection in 45 high-income countries. The results showed that Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Iceland, Italy, Japan, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom are “in the green” (on target for 2030).

Austria, Malta, the Netherlands, New Zealand, and South Korea are “in the yellow” (on target for 2040), and 28 remaining countries, including the United States, are “in the red,” with targets estimated to be met by 2050.

Compared with an analysis performed 2 years ago, South Korea moved from green to yellow, while Canada, Germany, and Sweden moved from red to green.

Researchers say that the countries moving the needle are the ones addressing barriers to care.

EASL: Eliminate barriers to treatment

During this week’s Congress, the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) launched a policy statement recommending breaking down all barriers that prevent people who inject drugs from getting access to hepatitis C treatment, including encouragement of laws and policies that “decriminalize drug use, drug possession and drug users themselves,” said statement coauthor Mojca Maticic, MD, PhD, University of Ljubljana, Slovenia.

“To reach the desired WHO goal, combining decriminalization of personal drug consumption and integrated interventions that include hepatitis C testing and treatment should be implemented,” she added. We need to adopt “an approach based on public health promotion, respect for human rights, and evidence.”

Although harm reduction is the top strategy for making 2030 targets, having precision data also helps a lot.

“High-quality data and harm-reduction innovation to curb the overdose crisis has moved us out of the red and into the green,” Canadian researcher Jordan Feld, MD, MPH, University of Toronto, said in an interview. He points to British Columbia, Canada’s third-most populous province, putting harm reduction programs in place as key to Canadian progress.

“Given the increasing opioid epidemic, you’re creating yourself a bigger problem if you don’t treat this population,” Dr. Feld said. When a person needs 6 months to get sober in order to be treated for HCV, that’s more potential time to pass the infection to others. His study, also presented at ILC this week, outlines anticipated timing of hepatitis C in Canada’s four most populous provinces (Ontario, Quebec, British Columbia, and Alberta), and shows British Columbia will reach targets by 2028.

Lifting all restrictions clearly helps, Dr. Sanchez Gonzalez reported. He pointed to Sweden as a good example, a country that recently lifted HCV treatment restrictions for individuals living with fibrosis. Sweden moved from a red to a green spot in this analysis and is now on target for 2030.

“As long as everyone who needs treatment gets treatment, you can make tremendous progress,” he said.

Keeping track is also essential to moving the needle. Since the WHO has no enforcement power, “these studies, which offer a report card of progress, really matter,” Dr. Sanchez Gonzalez explained. When a country knows where they stand, they are more likely to take action to change. “Nobody likes to be shown in the red.”

Still, “it’s not a shaming exercise,” he said. It’s about starting a conversation, showing who’s on track, and sharing how to get on track. “Knowing that there is something in your power to move the needle toward elimination by learning from your neighbors is powerful – often, it just takes political will.”

Dr. Feld has received consulting fees from AbbVie. Dr. Sanchez Gonzalez is on staff as the Director of Economics at AbbVie. Dr. Maticic has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Help your patients better understand the risks and treatment for hepatitis C by sharing AGA GI Patient Center education at http://ow.ly/xV2S30r8L29.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Many advanced countries missing targets for HCV elimination

Eleven high-income countries are on track to meet World Health Organization targets to eliminate hepatitis C infection by 2030, compared with 9 countries 2 years ago, researchers reported. But 28 countries, including the United States, are not expected to eliminate HCV until 2050.

“In the countries making progress, the common elements are political will, a clear national plan, and easing of restrictions on the cascade of care and testing,” Yuri Sanchez Gonzalez, PhD, director of health economics and outcomes research for biopharmaceutical company AbbVie said in an interview. That would include offering hepatitis C treatment to individuals who have liver fibrosis and those struggling with sobriety, he said. “We can’t overstate how much this is a massive driver of the hepatitis C epidemic.”

His research, presented at the digital edition of the International Liver Congress this week, showed more countries on target than in a study published 2 years ago in Liver International . “But it’s not enough,” Dr. Sanchez Gonzalez said. “We know that more than 80% of infections are in people who inject drugs. Stigmatization of drug use is still a very major issue.” Despite data clearly showing that countries who have harm-reduction programs make progress, “in many countries these programs are still illegal.”

To evaluate which countries are on target to eliminate hepatitis C by 2030, researchers performed Markov disease progression models of HCV infection in 45 high-income countries. The results showed that Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Iceland, Italy, Japan, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom are “in the green” (on target for 2030).

Austria, Malta, the Netherlands, New Zealand, and South Korea are “in the yellow” (on target for 2040), and 28 remaining countries, including the United States, are “in the red,” with targets estimated to be met by 2050.

Compared with an analysis performed 2 years ago, South Korea moved from green to yellow, while Canada, Germany, and Sweden moved from red to green.

Researchers say that the countries moving the needle are the ones addressing barriers to care.

EASL: Eliminate barriers to treatment

During this week’s Congress, the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) launched a policy statement recommending breaking down all barriers that prevent people who inject drugs from getting access to hepatitis C treatment, including encouragement of laws and policies that “decriminalize drug use, drug possession and drug users themselves,” said statement coauthor Mojca Maticic, MD, PhD, University of Ljubljana, Slovenia.

“To reach the desired WHO goal, combining decriminalization of personal drug consumption and integrated interventions that include hepatitis C testing and treatment should be implemented,” she added. We need to adopt “an approach based on public health promotion, respect for human rights, and evidence.”

Although harm reduction is the top strategy for making 2030 targets, having precision data also helps a lot.

“High-quality data and harm-reduction innovation to curb the overdose crisis has moved us out of the red and into the green,” Canadian researcher Jordan Feld, MD, MPH, University of Toronto, said in an interview. He points to British Columbia, Canada’s third-most populous province, putting harm reduction programs in place as key to Canadian progress.

“Given the increasing opioid epidemic, you’re creating yourself a bigger problem if you don’t treat this population,” Dr. Feld said. When a person needs 6 months to get sober in order to be treated for HCV, that’s more potential time to pass the infection to others. His study, also presented at ILC this week, outlines anticipated timing of hepatitis C in Canada’s four most populous provinces (Ontario, Quebec, British Columbia, and Alberta), and shows British Columbia will reach targets by 2028.

Lifting all restrictions clearly helps, Dr. Sanchez Gonzalez reported. He pointed to Sweden as a good example, a country that recently lifted HCV treatment restrictions for individuals living with fibrosis. Sweden moved from a red to a green spot in this analysis and is now on target for 2030.

“As long as everyone who needs treatment gets treatment, you can make tremendous progress,” he said.

Keeping track is also essential to moving the needle. Since the WHO has no enforcement power, “these studies, which offer a report card of progress, really matter,” Dr. Sanchez Gonzalez explained. When a country knows where they stand, they are more likely to take action to change. “Nobody likes to be shown in the red.”

Still, “it’s not a shaming exercise,” he said. It’s about starting a conversation, showing who’s on track, and sharing how to get on track. “Knowing that there is something in your power to move the needle toward elimination by learning from your neighbors is powerful – often, it just takes political will.”

Dr. Feld has received consulting fees from AbbVie. Dr. Sanchez Gonzalez is on staff as the Director of Economics at AbbVie. Dr. Maticic has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Eleven high-income countries are on track to meet World Health Organization targets to eliminate hepatitis C infection by 2030, compared with 9 countries 2 years ago, researchers reported. But 28 countries, including the United States, are not expected to eliminate HCV until 2050.

“In the countries making progress, the common elements are political will, a clear national plan, and easing of restrictions on the cascade of care and testing,” Yuri Sanchez Gonzalez, PhD, director of health economics and outcomes research for biopharmaceutical company AbbVie said in an interview. That would include offering hepatitis C treatment to individuals who have liver fibrosis and those struggling with sobriety, he said. “We can’t overstate how much this is a massive driver of the hepatitis C epidemic.”

His research, presented at the digital edition of the International Liver Congress this week, showed more countries on target than in a study published 2 years ago in Liver International . “But it’s not enough,” Dr. Sanchez Gonzalez said. “We know that more than 80% of infections are in people who inject drugs. Stigmatization of drug use is still a very major issue.” Despite data clearly showing that countries who have harm-reduction programs make progress, “in many countries these programs are still illegal.”

To evaluate which countries are on target to eliminate hepatitis C by 2030, researchers performed Markov disease progression models of HCV infection in 45 high-income countries. The results showed that Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Iceland, Italy, Japan, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom are “in the green” (on target for 2030).

Austria, Malta, the Netherlands, New Zealand, and South Korea are “in the yellow” (on target for 2040), and 28 remaining countries, including the United States, are “in the red,” with targets estimated to be met by 2050.

Compared with an analysis performed 2 years ago, South Korea moved from green to yellow, while Canada, Germany, and Sweden moved from red to green.

Researchers say that the countries moving the needle are the ones addressing barriers to care.

EASL: Eliminate barriers to treatment

During this week’s Congress, the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) launched a policy statement recommending breaking down all barriers that prevent people who inject drugs from getting access to hepatitis C treatment, including encouragement of laws and policies that “decriminalize drug use, drug possession and drug users themselves,” said statement coauthor Mojca Maticic, MD, PhD, University of Ljubljana, Slovenia.

“To reach the desired WHO goal, combining decriminalization of personal drug consumption and integrated interventions that include hepatitis C testing and treatment should be implemented,” she added. We need to adopt “an approach based on public health promotion, respect for human rights, and evidence.”

Although harm reduction is the top strategy for making 2030 targets, having precision data also helps a lot.

“High-quality data and harm-reduction innovation to curb the overdose crisis has moved us out of the red and into the green,” Canadian researcher Jordan Feld, MD, MPH, University of Toronto, said in an interview. He points to British Columbia, Canada’s third-most populous province, putting harm reduction programs in place as key to Canadian progress.

“Given the increasing opioid epidemic, you’re creating yourself a bigger problem if you don’t treat this population,” Dr. Feld said. When a person needs 6 months to get sober in order to be treated for HCV, that’s more potential time to pass the infection to others. His study, also presented at ILC this week, outlines anticipated timing of hepatitis C in Canada’s four most populous provinces (Ontario, Quebec, British Columbia, and Alberta), and shows British Columbia will reach targets by 2028.

Lifting all restrictions clearly helps, Dr. Sanchez Gonzalez reported. He pointed to Sweden as a good example, a country that recently lifted HCV treatment restrictions for individuals living with fibrosis. Sweden moved from a red to a green spot in this analysis and is now on target for 2030.

“As long as everyone who needs treatment gets treatment, you can make tremendous progress,” he said.

Keeping track is also essential to moving the needle. Since the WHO has no enforcement power, “these studies, which offer a report card of progress, really matter,” Dr. Sanchez Gonzalez explained. When a country knows where they stand, they are more likely to take action to change. “Nobody likes to be shown in the red.”

Still, “it’s not a shaming exercise,” he said. It’s about starting a conversation, showing who’s on track, and sharing how to get on track. “Knowing that there is something in your power to move the needle toward elimination by learning from your neighbors is powerful – often, it just takes political will.”

Dr. Feld has received consulting fees from AbbVie. Dr. Sanchez Gonzalez is on staff as the Director of Economics at AbbVie. Dr. Maticic has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Eleven high-income countries are on track to meet World Health Organization targets to eliminate hepatitis C infection by 2030, compared with 9 countries 2 years ago, researchers reported. But 28 countries, including the United States, are not expected to eliminate HCV until 2050.

“In the countries making progress, the common elements are political will, a clear national plan, and easing of restrictions on the cascade of care and testing,” Yuri Sanchez Gonzalez, PhD, director of health economics and outcomes research for biopharmaceutical company AbbVie said in an interview. That would include offering hepatitis C treatment to individuals who have liver fibrosis and those struggling with sobriety, he said. “We can’t overstate how much this is a massive driver of the hepatitis C epidemic.”

His research, presented at the digital edition of the International Liver Congress this week, showed more countries on target than in a study published 2 years ago in Liver International . “But it’s not enough,” Dr. Sanchez Gonzalez said. “We know that more than 80% of infections are in people who inject drugs. Stigmatization of drug use is still a very major issue.” Despite data clearly showing that countries who have harm-reduction programs make progress, “in many countries these programs are still illegal.”

To evaluate which countries are on target to eliminate hepatitis C by 2030, researchers performed Markov disease progression models of HCV infection in 45 high-income countries. The results showed that Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Iceland, Italy, Japan, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom are “in the green” (on target for 2030).

Austria, Malta, the Netherlands, New Zealand, and South Korea are “in the yellow” (on target for 2040), and 28 remaining countries, including the United States, are “in the red,” with targets estimated to be met by 2050.

Compared with an analysis performed 2 years ago, South Korea moved from green to yellow, while Canada, Germany, and Sweden moved from red to green.

Researchers say that the countries moving the needle are the ones addressing barriers to care.

EASL: Eliminate barriers to treatment

During this week’s Congress, the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) launched a policy statement recommending breaking down all barriers that prevent people who inject drugs from getting access to hepatitis C treatment, including encouragement of laws and policies that “decriminalize drug use, drug possession and drug users themselves,” said statement coauthor Mojca Maticic, MD, PhD, University of Ljubljana, Slovenia.

“To reach the desired WHO goal, combining decriminalization of personal drug consumption and integrated interventions that include hepatitis C testing and treatment should be implemented,” she added. We need to adopt “an approach based on public health promotion, respect for human rights, and evidence.”

Although harm reduction is the top strategy for making 2030 targets, having precision data also helps a lot.

“High-quality data and harm-reduction innovation to curb the overdose crisis has moved us out of the red and into the green,” Canadian researcher Jordan Feld, MD, MPH, University of Toronto, said in an interview. He points to British Columbia, Canada’s third-most populous province, putting harm reduction programs in place as key to Canadian progress.

“Given the increasing opioid epidemic, you’re creating yourself a bigger problem if you don’t treat this population,” Dr. Feld said. When a person needs 6 months to get sober in order to be treated for HCV, that’s more potential time to pass the infection to others. His study, also presented at ILC this week, outlines anticipated timing of hepatitis C in Canada’s four most populous provinces (Ontario, Quebec, British Columbia, and Alberta), and shows British Columbia will reach targets by 2028.

Lifting all restrictions clearly helps, Dr. Sanchez Gonzalez reported. He pointed to Sweden as a good example, a country that recently lifted HCV treatment restrictions for individuals living with fibrosis. Sweden moved from a red to a green spot in this analysis and is now on target for 2030.

“As long as everyone who needs treatment gets treatment, you can make tremendous progress,” he said.

Keeping track is also essential to moving the needle. Since the WHO has no enforcement power, “these studies, which offer a report card of progress, really matter,” Dr. Sanchez Gonzalez explained. When a country knows where they stand, they are more likely to take action to change. “Nobody likes to be shown in the red.”

Still, “it’s not a shaming exercise,” he said. It’s about starting a conversation, showing who’s on track, and sharing how to get on track. “Knowing that there is something in your power to move the needle toward elimination by learning from your neighbors is powerful – often, it just takes political will.”

Dr. Feld has received consulting fees from AbbVie. Dr. Sanchez Gonzalez is on staff as the Director of Economics at AbbVie. Dr. Maticic has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Repeat FIB-4 blood tests help predict cirrhosis

Repeat Fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) scores can be used to identify people at greatest risk for cirrhosis of the liver, new research shows.

“Done repeatedly, this test can improve prediction capacity to identify who will develop cirrhosis of the liver later in life,” said lead researcher Hannes Hagström, MD, from the Karolinska University Hospital in Stockholm.

A FIB-4 score that rises from one test to the next indicates that a person is at increased risk for severe liver disease, whereas a score that drops indicates a decreased risk, he told Medscape Medical News. The study results — published online July 1 in the Journal of Hepatology, was presented at the Digital International Liver Congress 2020.

The noninvasive, widely available, cheap FIB-4 test — which is calculated on the basis of age, transaminase level, and platelet count — is commonly used to identify the risk for advanced fibrosis in liver disease, but it has not been used to predict future risk.

To evaluate risk for cirrhosis, Hagström and his colleagues looked at 812,073 blood tests performed from 1985 to 1996 on people enrolled in the Swedish Apolipoprotein Mortality Risk (AMORIS) study.

They excluded people younger than 35 years and older than 79 years and anyone with a diagnosis of any liver disease at baseline.

The 40,729 people who had two FIB-4 measurements taken less than 5 years apart were included in the analysis. Test results were categorized into three risk groups: low (<1.30), intermediate (1.30 - 2.67), and high (>2.67).

After a median of 16.2 years, 11,929 people in the study cohort had died and 581 had a severe liver disease event.

Severe liver disease events were more common in people who had both tests categorized as high risk than in people who had both tests categorized as low risk (13.2% vs 1.0%; aHR, 17.04; 95% CI, 11.67 - 24.88).

The researchers found that a one-unit increase between the two test results was continuously predictive of a severe liver disease event (aHR, 1.81; 95% CI, 1.67 - 1.96).

One test not enough

The absolute risk for severe liver disease in the general population is 2%, but the FIB-4 score is elevated in about one-third of people in the general population.

“A lot of people who have increased levels of this biomarker will never develop cirrhosis,” Hagström told Medscape Medical News.

Although two FIB-4 scores might not identify everyone who will get cirrhosis, comparing scores provides insight into who is at greatest risk, he explained.

This information can be useful, particularly for primary care doctors. If you know that someone is at higher risk, “you can send that patient for a FibroScan, which is a much more sensitive measurement,” but also much more expensive. “Now we can better know who to send,” he said.

However, “the main problem is that these tests are not widely known” or used enough by primary care doctors, Hagström said.

A lack of knowledge about the utility of this test is a problem, agreed Jérôme Boursier, MD, PhD, from Angers University in France.

“The younger doctors are using these tests more often,” he told Medscape Medical News, but “the older doctors are not aware they exist.”

This study supports repeating the tests. “One test offers quite poor prediction,” Boursier said. But “when you have a higher score on a second one, this can help the conversation with the patient.”

Hagström and Boursier have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Repeat Fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) scores can be used to identify people at greatest risk for cirrhosis of the liver, new research shows.

“Done repeatedly, this test can improve prediction capacity to identify who will develop cirrhosis of the liver later in life,” said lead researcher Hannes Hagström, MD, from the Karolinska University Hospital in Stockholm.

A FIB-4 score that rises from one test to the next indicates that a person is at increased risk for severe liver disease, whereas a score that drops indicates a decreased risk, he told Medscape Medical News. The study results — published online July 1 in the Journal of Hepatology, was presented at the Digital International Liver Congress 2020.

The noninvasive, widely available, cheap FIB-4 test — which is calculated on the basis of age, transaminase level, and platelet count — is commonly used to identify the risk for advanced fibrosis in liver disease, but it has not been used to predict future risk.

To evaluate risk for cirrhosis, Hagström and his colleagues looked at 812,073 blood tests performed from 1985 to 1996 on people enrolled in the Swedish Apolipoprotein Mortality Risk (AMORIS) study.

They excluded people younger than 35 years and older than 79 years and anyone with a diagnosis of any liver disease at baseline.

The 40,729 people who had two FIB-4 measurements taken less than 5 years apart were included in the analysis. Test results were categorized into three risk groups: low (<1.30), intermediate (1.30 - 2.67), and high (>2.67).

After a median of 16.2 years, 11,929 people in the study cohort had died and 581 had a severe liver disease event.

Severe liver disease events were more common in people who had both tests categorized as high risk than in people who had both tests categorized as low risk (13.2% vs 1.0%; aHR, 17.04; 95% CI, 11.67 - 24.88).

The researchers found that a one-unit increase between the two test results was continuously predictive of a severe liver disease event (aHR, 1.81; 95% CI, 1.67 - 1.96).

One test not enough

The absolute risk for severe liver disease in the general population is 2%, but the FIB-4 score is elevated in about one-third of people in the general population.

“A lot of people who have increased levels of this biomarker will never develop cirrhosis,” Hagström told Medscape Medical News.

Although two FIB-4 scores might not identify everyone who will get cirrhosis, comparing scores provides insight into who is at greatest risk, he explained.

This information can be useful, particularly for primary care doctors. If you know that someone is at higher risk, “you can send that patient for a FibroScan, which is a much more sensitive measurement,” but also much more expensive. “Now we can better know who to send,” he said.

However, “the main problem is that these tests are not widely known” or used enough by primary care doctors, Hagström said.

A lack of knowledge about the utility of this test is a problem, agreed Jérôme Boursier, MD, PhD, from Angers University in France.

“The younger doctors are using these tests more often,” he told Medscape Medical News, but “the older doctors are not aware they exist.”

This study supports repeating the tests. “One test offers quite poor prediction,” Boursier said. But “when you have a higher score on a second one, this can help the conversation with the patient.”

Hagström and Boursier have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Repeat Fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) scores can be used to identify people at greatest risk for cirrhosis of the liver, new research shows.

“Done repeatedly, this test can improve prediction capacity to identify who will develop cirrhosis of the liver later in life,” said lead researcher Hannes Hagström, MD, from the Karolinska University Hospital in Stockholm.

A FIB-4 score that rises from one test to the next indicates that a person is at increased risk for severe liver disease, whereas a score that drops indicates a decreased risk, he told Medscape Medical News. The study results — published online July 1 in the Journal of Hepatology, was presented at the Digital International Liver Congress 2020.

The noninvasive, widely available, cheap FIB-4 test — which is calculated on the basis of age, transaminase level, and platelet count — is commonly used to identify the risk for advanced fibrosis in liver disease, but it has not been used to predict future risk.

To evaluate risk for cirrhosis, Hagström and his colleagues looked at 812,073 blood tests performed from 1985 to 1996 on people enrolled in the Swedish Apolipoprotein Mortality Risk (AMORIS) study.

They excluded people younger than 35 years and older than 79 years and anyone with a diagnosis of any liver disease at baseline.

The 40,729 people who had two FIB-4 measurements taken less than 5 years apart were included in the analysis. Test results were categorized into three risk groups: low (<1.30), intermediate (1.30 - 2.67), and high (>2.67).

After a median of 16.2 years, 11,929 people in the study cohort had died and 581 had a severe liver disease event.

Severe liver disease events were more common in people who had both tests categorized as high risk than in people who had both tests categorized as low risk (13.2% vs 1.0%; aHR, 17.04; 95% CI, 11.67 - 24.88).

The researchers found that a one-unit increase between the two test results was continuously predictive of a severe liver disease event (aHR, 1.81; 95% CI, 1.67 - 1.96).

One test not enough

The absolute risk for severe liver disease in the general population is 2%, but the FIB-4 score is elevated in about one-third of people in the general population.

“A lot of people who have increased levels of this biomarker will never develop cirrhosis,” Hagström told Medscape Medical News.

Although two FIB-4 scores might not identify everyone who will get cirrhosis, comparing scores provides insight into who is at greatest risk, he explained.

This information can be useful, particularly for primary care doctors. If you know that someone is at higher risk, “you can send that patient for a FibroScan, which is a much more sensitive measurement,” but also much more expensive. “Now we can better know who to send,” he said.

However, “the main problem is that these tests are not widely known” or used enough by primary care doctors, Hagström said.

A lack of knowledge about the utility of this test is a problem, agreed Jérôme Boursier, MD, PhD, from Angers University in France.

“The younger doctors are using these tests more often,” he told Medscape Medical News, but “the older doctors are not aware they exist.”

This study supports repeating the tests. “One test offers quite poor prediction,” Boursier said. But “when you have a higher score on a second one, this can help the conversation with the patient.”

Hagström and Boursier have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Fecal transplant shows promise in reducing alcohol craving

Fecal microbiota transplantation results in a short-term reduction in alcohol craving in patients with alcohol-induced cirrhosis who can’t stop drinking, results from a new study show.

And that reduction could lead to a better psychosocial quality of life for patients with cirrhosis and alcohol use disorder, said investigator Jasmohan Bajaj, MD, from Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond.

“This is the most common addiction disorder worldwide, but we have nothing to treat these patients with,” he said.

Cirrhosis is associated with an altered gut-brain axis. It leads to organ damage in several parts of the body, including the brain, gut, pancreas, and liver. This makes changing the gut microbes “an attractive target,” Dr. Bajaj said at the Digital International Liver Congress 2020.

For their phase 1, double-blind study, he and his colleagues assessed 20 men from a Virginia veteran’s hospital with untreatable alcohol use disorder who were not eligible for liver transplantation.

All had failed behavioral or pharmacologic therapy and were unwilling to try again. “That’s what made them good candidates to try something new,” Dr. Bajaj said during a press briefing.

Mean age in the study cohort was 65 years, mean Model for End-Stage Liver disease score was 8.9, and demographic characteristics were similar between the 10 men randomly assigned to fecal transplantation and the 10 assigned to placebo. One man in each group dropped out of the study.

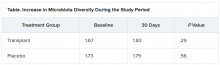

The investigators evaluated cravings, microbiota, and quality of life during the 30-day study period.

At day 15, significantly more men in the transplant group than in the placebo group experienced a reduction in alcohol cravings (90% vs. 30%).

At 30 days, levels of creatinine, serum interleukin-6, and lipopolysaccharide-binding protein were lower in the transplant group than in the placebo group. In addition, levels of butyrate and isobutyrate increased, as did cognition and quality of life scores.

There was also a decrease in urinary ethyl glucuronide in the transplant group, which “is the objective criteria for alcohol intake,” Dr. Bajaj reported, noting that there was no change in ethyl glucuronide in the placebo group.

The increase in microbiota diversity was significant in the transplant group but not in the placebo group. Alistipes, Odoribacter, and Roseburia were more abundant in the transplant group than in the placebo group.

During the 30-day study period, two men in the placebo group required medical attention, one for hyponatremia and the other for atrial fibrillation. However, no adverse events were seen in any men in the transplant group. “This was the No. 1 result,” Dr. Bajaj said.

Liver disease and the microbiome

“Understanding of interactions between the human and microbiome genome [metagenome] in health and disease has represented one of the major areas of progress in the last few years,” said Luca Valenti, MD, from the University of Milan, who is a member of the scientific committee of the European Association the Study of the Liver, which organized the congress.

“These studies lay the groundwork for the exploitation of this new knowledge for the treatment of liver disease,” he said.

“We are [now] diagnosing liver disease and the stages of liver disease based on microbiome changes,” said Jonel Trebicka, MD, PhD, from University Hospital Frankfurt (Germany), who chaired a session at the congress on the role of the microbiome in liver disease.

“This and other studies have shown us that the microbiome itself may influence liver disease,” he added.

Dr. Bajaj is considered one of the world’s experts on cirrhosis and the microbiome, Dr. Trebicka explained. Last year, Dr. Bajaj and his team demonstrated that fecal microbiota transplantation can reduce the incidence of recurrent hepatic encephalopathy, as reported by Medscape Medical News.

The current study also “shows clearly that the microbiome plays a role in craving. FMT reduces the desire for alcohol,” said Dr. Trebicka.

“The way to the brain is through the gut,” Dr. Bajaj said.

Dr. Bajaj, Dr. Trebicka, and Dr. Valenti disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Fecal microbiota transplantation results in a short-term reduction in alcohol craving in patients with alcohol-induced cirrhosis who can’t stop drinking, results from a new study show.

And that reduction could lead to a better psychosocial quality of life for patients with cirrhosis and alcohol use disorder, said investigator Jasmohan Bajaj, MD, from Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond.

“This is the most common addiction disorder worldwide, but we have nothing to treat these patients with,” he said.

Cirrhosis is associated with an altered gut-brain axis. It leads to organ damage in several parts of the body, including the brain, gut, pancreas, and liver. This makes changing the gut microbes “an attractive target,” Dr. Bajaj said at the Digital International Liver Congress 2020.

For their phase 1, double-blind study, he and his colleagues assessed 20 men from a Virginia veteran’s hospital with untreatable alcohol use disorder who were not eligible for liver transplantation.

All had failed behavioral or pharmacologic therapy and were unwilling to try again. “That’s what made them good candidates to try something new,” Dr. Bajaj said during a press briefing.

Mean age in the study cohort was 65 years, mean Model for End-Stage Liver disease score was 8.9, and demographic characteristics were similar between the 10 men randomly assigned to fecal transplantation and the 10 assigned to placebo. One man in each group dropped out of the study.

The investigators evaluated cravings, microbiota, and quality of life during the 30-day study period.

At day 15, significantly more men in the transplant group than in the placebo group experienced a reduction in alcohol cravings (90% vs. 30%).

At 30 days, levels of creatinine, serum interleukin-6, and lipopolysaccharide-binding protein were lower in the transplant group than in the placebo group. In addition, levels of butyrate and isobutyrate increased, as did cognition and quality of life scores.

There was also a decrease in urinary ethyl glucuronide in the transplant group, which “is the objective criteria for alcohol intake,” Dr. Bajaj reported, noting that there was no change in ethyl glucuronide in the placebo group.

The increase in microbiota diversity was significant in the transplant group but not in the placebo group. Alistipes, Odoribacter, and Roseburia were more abundant in the transplant group than in the placebo group.

During the 30-day study period, two men in the placebo group required medical attention, one for hyponatremia and the other for atrial fibrillation. However, no adverse events were seen in any men in the transplant group. “This was the No. 1 result,” Dr. Bajaj said.

Liver disease and the microbiome

“Understanding of interactions between the human and microbiome genome [metagenome] in health and disease has represented one of the major areas of progress in the last few years,” said Luca Valenti, MD, from the University of Milan, who is a member of the scientific committee of the European Association the Study of the Liver, which organized the congress.

“These studies lay the groundwork for the exploitation of this new knowledge for the treatment of liver disease,” he said.

“We are [now] diagnosing liver disease and the stages of liver disease based on microbiome changes,” said Jonel Trebicka, MD, PhD, from University Hospital Frankfurt (Germany), who chaired a session at the congress on the role of the microbiome in liver disease.

“This and other studies have shown us that the microbiome itself may influence liver disease,” he added.

Dr. Bajaj is considered one of the world’s experts on cirrhosis and the microbiome, Dr. Trebicka explained. Last year, Dr. Bajaj and his team demonstrated that fecal microbiota transplantation can reduce the incidence of recurrent hepatic encephalopathy, as reported by Medscape Medical News.

The current study also “shows clearly that the microbiome plays a role in craving. FMT reduces the desire for alcohol,” said Dr. Trebicka.

“The way to the brain is through the gut,” Dr. Bajaj said.

Dr. Bajaj, Dr. Trebicka, and Dr. Valenti disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Fecal microbiota transplantation results in a short-term reduction in alcohol craving in patients with alcohol-induced cirrhosis who can’t stop drinking, results from a new study show.

And that reduction could lead to a better psychosocial quality of life for patients with cirrhosis and alcohol use disorder, said investigator Jasmohan Bajaj, MD, from Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond.

“This is the most common addiction disorder worldwide, but we have nothing to treat these patients with,” he said.

Cirrhosis is associated with an altered gut-brain axis. It leads to organ damage in several parts of the body, including the brain, gut, pancreas, and liver. This makes changing the gut microbes “an attractive target,” Dr. Bajaj said at the Digital International Liver Congress 2020.

For their phase 1, double-blind study, he and his colleagues assessed 20 men from a Virginia veteran’s hospital with untreatable alcohol use disorder who were not eligible for liver transplantation.

All had failed behavioral or pharmacologic therapy and were unwilling to try again. “That’s what made them good candidates to try something new,” Dr. Bajaj said during a press briefing.

Mean age in the study cohort was 65 years, mean Model for End-Stage Liver disease score was 8.9, and demographic characteristics were similar between the 10 men randomly assigned to fecal transplantation and the 10 assigned to placebo. One man in each group dropped out of the study.

The investigators evaluated cravings, microbiota, and quality of life during the 30-day study period.

At day 15, significantly more men in the transplant group than in the placebo group experienced a reduction in alcohol cravings (90% vs. 30%).

At 30 days, levels of creatinine, serum interleukin-6, and lipopolysaccharide-binding protein were lower in the transplant group than in the placebo group. In addition, levels of butyrate and isobutyrate increased, as did cognition and quality of life scores.

There was also a decrease in urinary ethyl glucuronide in the transplant group, which “is the objective criteria for alcohol intake,” Dr. Bajaj reported, noting that there was no change in ethyl glucuronide in the placebo group.

The increase in microbiota diversity was significant in the transplant group but not in the placebo group. Alistipes, Odoribacter, and Roseburia were more abundant in the transplant group than in the placebo group.

During the 30-day study period, two men in the placebo group required medical attention, one for hyponatremia and the other for atrial fibrillation. However, no adverse events were seen in any men in the transplant group. “This was the No. 1 result,” Dr. Bajaj said.

Liver disease and the microbiome

“Understanding of interactions between the human and microbiome genome [metagenome] in health and disease has represented one of the major areas of progress in the last few years,” said Luca Valenti, MD, from the University of Milan, who is a member of the scientific committee of the European Association the Study of the Liver, which organized the congress.

“These studies lay the groundwork for the exploitation of this new knowledge for the treatment of liver disease,” he said.

“We are [now] diagnosing liver disease and the stages of liver disease based on microbiome changes,” said Jonel Trebicka, MD, PhD, from University Hospital Frankfurt (Germany), who chaired a session at the congress on the role of the microbiome in liver disease.

“This and other studies have shown us that the microbiome itself may influence liver disease,” he added.

Dr. Bajaj is considered one of the world’s experts on cirrhosis and the microbiome, Dr. Trebicka explained. Last year, Dr. Bajaj and his team demonstrated that fecal microbiota transplantation can reduce the incidence of recurrent hepatic encephalopathy, as reported by Medscape Medical News.

The current study also “shows clearly that the microbiome plays a role in craving. FMT reduces the desire for alcohol,” said Dr. Trebicka.

“The way to the brain is through the gut,” Dr. Bajaj said.

Dr. Bajaj, Dr. Trebicka, and Dr. Valenti disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Pulmonary rehab reduces COPD readmissions

Pulmonary rehabilitation reduces the likelihood that patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) will be readmitted to the hospital in the year after discharge by 33%, new research shows, but few patients participate in those programs.

In fact, in a retrospective cohort of 197,376 patients from 4446 hospitals, only 1.5% of patients initiated pulmonary rehabilitation in the 90 days after hospital discharge.

“This is a striking finding,” said Mihaela Stefan, PhD, from the University of Massachusetts Medical School–Baystate in Springfield. “Our study demonstrates that we need to increase access to rehabilitation to reduce the risk of readmissions.”

Not enough patients are initiating rehabilitation, but the onus is not only on them; the system is failing them. “We wanted to understand how much pulmonary rehabilitation lowers the readmission rate,” Stefan told Medscape Medical News.

So she and her colleagues examined the records of patients who were hospitalized for COPD in 2014 to see whether they had begun rehabilitation in the 90 days after discharge and whether they were readmitted to the hospital in the subsequent 12 months.

Patients who were unlikely to initiate pulmonary rehabilitation — such as those with dementia or metastatic cancer and those discharged to hospice care or a nursing home — were excluded from the analysis, Stefan said during her presentation at the study results at the virtual American Thoracic Society (ATS) 2020 International Conference.

The risk analysis was complex because many patients died before the year was out, and “a patient who dies has no risk of being readmitted,” she explained. Selection bias was also a factor because patients who do pulmonary rehab tend to be in better shape.

The researchers used propensity score matching and Anderson–Gill models of cumulative rehospitalizations or death at 1 year with time-varying exposure to pulmonary rehabilitation to account for clustering of individual events and adjust for covariates. “It was a complicated risk analysis,” she said.

In the year after discharge, 130,660 patients (66%) were readmitted to the hospital. The rate of rehospitalization was lower for those who initiated rehabilitation than for those who did not (59% vs 66%), as was the mean number of readmissions per patient (1.4 vs 1.8).

Rehabilitation was associated with a lower risk for readmission or death (hazard ratio, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.66 - 0.69).

“We know the referral rates are low and that pulmonary rehabilitation is effective in clinical trials,” said Stefan, and now “we see that pulmonary rehabilitation is effective when you look at patients in real life.”

From a provider perspective, “we need to make sure that hospitals get more money for pulmonary rehabilitation. Cardiac rehabilitation is paid for,” she explained. "But pulmonary rehab is not a lucrative business. I don›t know why the CMS pays more for cardiac."

A rehabilitation program generally consists of 36 sessions, held two or three times a week, and many patients can’t afford that on their own, she noted. Transportation is another huge issue.

A recent study in which semi-structured interviews were conducted with 15 COPD patients showed that the main barriers to enrollment in a pulmonary rehabilitation program are lack of awareness, family obligations, transportation, and lack of motivation, said Stefan, who was involved in that research.

Telehealth rehabilitation programs might become more available in the near future, given the COVID pandemic. But “currently, Medicare doesn’t pay for telerehab,” she said. Virtual sessions might attract more patients, but lack of computer access and training could present another barrier for some.

PAH rehab

Uptake for pulmonary rehabilitation is as low for patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) as it is for those with COPD, according to another study presented at the virtual ATS meeting.

An examination of the electronic health records of 111,356 veterans who experienced incident PAH from 2010 to 2016 showed that only 1,737 (1.6%) followed through on pulmonary rehabilitation.

“Exercise therapy is safe and effective at improving outcomes,” lead author Thomas Cascino, MD, from the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, said in an ATS press release. “Recognizing that it is being underutilized is a necessary first step in working toward increasing patient access to rehab.

His group is currently working on a trial for home-based rehabilitation “using wearable technology as a means to expand access for people unable to come to center-based rehab for a variety of reasons,” he explained.

“The goal of all our treatments is to help people feel better and live longer,” Cascino added.

Stefan and Cascino have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Pulmonary rehabilitation reduces the likelihood that patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) will be readmitted to the hospital in the year after discharge by 33%, new research shows, but few patients participate in those programs.

In fact, in a retrospective cohort of 197,376 patients from 4446 hospitals, only 1.5% of patients initiated pulmonary rehabilitation in the 90 days after hospital discharge.

“This is a striking finding,” said Mihaela Stefan, PhD, from the University of Massachusetts Medical School–Baystate in Springfield. “Our study demonstrates that we need to increase access to rehabilitation to reduce the risk of readmissions.”

Not enough patients are initiating rehabilitation, but the onus is not only on them; the system is failing them. “We wanted to understand how much pulmonary rehabilitation lowers the readmission rate,” Stefan told Medscape Medical News.

So she and her colleagues examined the records of patients who were hospitalized for COPD in 2014 to see whether they had begun rehabilitation in the 90 days after discharge and whether they were readmitted to the hospital in the subsequent 12 months.

Patients who were unlikely to initiate pulmonary rehabilitation — such as those with dementia or metastatic cancer and those discharged to hospice care or a nursing home — were excluded from the analysis, Stefan said during her presentation at the study results at the virtual American Thoracic Society (ATS) 2020 International Conference.

The risk analysis was complex because many patients died before the year was out, and “a patient who dies has no risk of being readmitted,” she explained. Selection bias was also a factor because patients who do pulmonary rehab tend to be in better shape.

The researchers used propensity score matching and Anderson–Gill models of cumulative rehospitalizations or death at 1 year with time-varying exposure to pulmonary rehabilitation to account for clustering of individual events and adjust for covariates. “It was a complicated risk analysis,” she said.

In the year after discharge, 130,660 patients (66%) were readmitted to the hospital. The rate of rehospitalization was lower for those who initiated rehabilitation than for those who did not (59% vs 66%), as was the mean number of readmissions per patient (1.4 vs 1.8).

Rehabilitation was associated with a lower risk for readmission or death (hazard ratio, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.66 - 0.69).

“We know the referral rates are low and that pulmonary rehabilitation is effective in clinical trials,” said Stefan, and now “we see that pulmonary rehabilitation is effective when you look at patients in real life.”

From a provider perspective, “we need to make sure that hospitals get more money for pulmonary rehabilitation. Cardiac rehabilitation is paid for,” she explained. "But pulmonary rehab is not a lucrative business. I don›t know why the CMS pays more for cardiac."

A rehabilitation program generally consists of 36 sessions, held two or three times a week, and many patients can’t afford that on their own, she noted. Transportation is another huge issue.

A recent study in which semi-structured interviews were conducted with 15 COPD patients showed that the main barriers to enrollment in a pulmonary rehabilitation program are lack of awareness, family obligations, transportation, and lack of motivation, said Stefan, who was involved in that research.

Telehealth rehabilitation programs might become more available in the near future, given the COVID pandemic. But “currently, Medicare doesn’t pay for telerehab,” she said. Virtual sessions might attract more patients, but lack of computer access and training could present another barrier for some.

PAH rehab

Uptake for pulmonary rehabilitation is as low for patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) as it is for those with COPD, according to another study presented at the virtual ATS meeting.

An examination of the electronic health records of 111,356 veterans who experienced incident PAH from 2010 to 2016 showed that only 1,737 (1.6%) followed through on pulmonary rehabilitation.

“Exercise therapy is safe and effective at improving outcomes,” lead author Thomas Cascino, MD, from the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, said in an ATS press release. “Recognizing that it is being underutilized is a necessary first step in working toward increasing patient access to rehab.

His group is currently working on a trial for home-based rehabilitation “using wearable technology as a means to expand access for people unable to come to center-based rehab for a variety of reasons,” he explained.

“The goal of all our treatments is to help people feel better and live longer,” Cascino added.

Stefan and Cascino have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Pulmonary rehabilitation reduces the likelihood that patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) will be readmitted to the hospital in the year after discharge by 33%, new research shows, but few patients participate in those programs.

In fact, in a retrospective cohort of 197,376 patients from 4446 hospitals, only 1.5% of patients initiated pulmonary rehabilitation in the 90 days after hospital discharge.

“This is a striking finding,” said Mihaela Stefan, PhD, from the University of Massachusetts Medical School–Baystate in Springfield. “Our study demonstrates that we need to increase access to rehabilitation to reduce the risk of readmissions.”

Not enough patients are initiating rehabilitation, but the onus is not only on them; the system is failing them. “We wanted to understand how much pulmonary rehabilitation lowers the readmission rate,” Stefan told Medscape Medical News.

So she and her colleagues examined the records of patients who were hospitalized for COPD in 2014 to see whether they had begun rehabilitation in the 90 days after discharge and whether they were readmitted to the hospital in the subsequent 12 months.

Patients who were unlikely to initiate pulmonary rehabilitation — such as those with dementia or metastatic cancer and those discharged to hospice care or a nursing home — were excluded from the analysis, Stefan said during her presentation at the study results at the virtual American Thoracic Society (ATS) 2020 International Conference.

The risk analysis was complex because many patients died before the year was out, and “a patient who dies has no risk of being readmitted,” she explained. Selection bias was also a factor because patients who do pulmonary rehab tend to be in better shape.

The researchers used propensity score matching and Anderson–Gill models of cumulative rehospitalizations or death at 1 year with time-varying exposure to pulmonary rehabilitation to account for clustering of individual events and adjust for covariates. “It was a complicated risk analysis,” she said.

In the year after discharge, 130,660 patients (66%) were readmitted to the hospital. The rate of rehospitalization was lower for those who initiated rehabilitation than for those who did not (59% vs 66%), as was the mean number of readmissions per patient (1.4 vs 1.8).

Rehabilitation was associated with a lower risk for readmission or death (hazard ratio, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.66 - 0.69).

“We know the referral rates are low and that pulmonary rehabilitation is effective in clinical trials,” said Stefan, and now “we see that pulmonary rehabilitation is effective when you look at patients in real life.”