User login

Pigmented lesion on the ear

A 65-year-old farmer came to the office with a pigmented lesion on his left ear; the lesion had been there for about 2 years. He noticed different shades of black developing in the lesion during the previous 3 months.

On physical examination, we observed a 13 mm x 7 mm asymmetrical dark-brown-to-black papule, with pigment fading at its borders, on the lower helix of the patient’s left ear. No ulceration was noted.

As an incidental finding, we noted accumulation of a yellowish waxy material in the left retroauricular area. The right ear was normal on examination, and no mucosal lesions were found. Lymph nodes of the retroauricular, submandibular, occipital, and supraclavicular areas were normal. An excisional biopsy was performed.

What is the diagnosis?

How would you manage this case?

FIGURE 1

Pigmented papule on the ear

Diagnosis: Malignant melanoma

Our patient’s excisional biopsy, which included 3-mm lateral margins, demonstrated clear architectural and cytological abnormalities consistent with superficial spreading malignant melanoma. Pronounced anisocytosis with prominent nucleoli and unevenly distributed melanin was noted, with atypical melanocytes extending into the papillary dermis. The Breslow thickness was 0.55 mm (Clark level II), and the TNM stage was T1a.

Incidence of malignant melanoma

The incidence of malignant melanoma has more than tripled among Caucasians in the US over the last 40 years; it is the fastest-growing1 and seventh most frequent cancer in the country.2 The risk of developing malignant melanoma is expected to reach 1 in 50 by 2010,3 increasing from 1 in 250 less than a quarter-century ago.1 Elderly men are particularly at risk.

Roughly 20% of melanomas develop in the head and neck regions, and of these approximately 7% to 14% are located on the external ear.4 Melanoma of the external ear most frequently develops on the left side (possibly due to increased sun exposure while driving), usually on the helix.1,4 In a small series by Benmeir et al,4 most patients reported having had an ear nevus whose features (size, color) began changing before diagnosis. Of note, only about one quarter of cutaneous melanomas are discovered directly by physicians.3 Moreover, neoplasms in certain regions of the ear may easily go unnoticed, causing a delay in diagnosis and treatment.1

Lesions are generally found in peripheral areas of the ear and are usually the superficial spreading type; however, nodular melanoma predominated in 1 relatively recent series.7 The lack of subcutaneous tissue on the external ear may contribute to the ease of invasion and poor prognosis identified in several reports.4,7 Hudson et al8 noted more deeply penetrating and thicker lesions at presentation on the external ear in comparison with malignant melanoma of other head and neck areas.

Risk factors

Risk factors for developing malignant melanoma include intense intermittent sunlight exposure (primarily UVB) and blistering sunburns at an early age; skin types and certain ethnicities with limited tanning capability; personal or family history of melanoma; multiple nevi; and immunosup-pression.3 The vast majority of malignant melanomas arise de novo, although very rarely a nevus (usually a giant congenital melanocytic nevus) may undergo malignant transformation.3

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of malignant melanoma includes atypical nevi, dermatofibromas, lentigos, basal and squamous cell carcinomas, keloids and hypertrophic scars, and seborrheic keratoses.2

Making an accurate diagnosis

The ABCD approach

The ABCD approach to recognizing potentially malignant melanotic lesions is evaluation for Asymmetry, Border irregularity, Color variegation, and Diameter >6 mm (roughly pencil eraser size). Patients who report recent changes in the characteristics of existing nevi should be examined carefully.

Biopsy, histology, dermatoscopy

Excisional biopsy and histologic examination are required for diagnosis, which is facilitated by histochemistry and immunohistochemistry techniques. Architectural criteria are of greater diagnostic significance than cytologic features, rendering fine- needle aspiration or curettage less helpful and unnecessary for diagnosis.3 Before excision, corresponding areas of lymphatic drainage should be examined, and subsequently a full-thickness biopsy with 2- to 5-mm lateral margins should be performed.9

Dermatoscopy is an excellent noninvasive method for in vivo examination of suspected melanomas, being a potentially powerful resource for general practitioners and dermatologists alike. In this procedure, the suspected melanoma is covered with mineral oil, alcohol, or water and viewed with a hand-held dermatoscope, which magnifies from 10 to 100 times, allowing visualization of structures at and below the skin surface. In comparison with clinical analysis, the sensitivity of dermatoscopic diagnosis is increased by 10% to 30%.3

Management: Surgical excision and special considerations

Difficulties in managing ear melanomas arise due to the ear’s importance in daily functioning and to patient’s cosmetic concerns. Initial reports of malignant melanoma of the external ear indicated a poorer prognosis compared with lesions in other areas,5,6 but subsequent studies did not corroborate these findings.

Surgical excision

Surgical excision is the standard of care for malignant melanoma. The World Health Organization recommends excision margins of 5 mm for in situ lesions, and 20 mm for melanomas >2.1 mm thick,10 although treatment of external ear lesions must be individualized given the thin skin and various anatomic subdivisions of the ear. Pockaj et al1 found margins of at least 10 mm to be associated with the lowest recurrence risk.

Several techniques have been employed in lesion excision and postexcisional defect repair, including wedge resection, partial and total auriculectomy, wide excision and skin grafting, and Mohs micrographic surgery.4 Wedge resection was associated in 1 study8 with significantly increased melanoma recurrence when compared with wide local excision using 10-mm margins or total auriculectomy.

Skin and subcutaneous tissue should always be excised, but perichondrium is generally spared unless involved with the tumor.1 However, Narayan et al11 suggested cartilaginous excision in melanomas >1 mm thick, regardless of the presence of tumor infiltration. Various types of flaps are used in reconstructing surgical defects.11

Lymph node dissection

Elective lymph node dissection, as well as superficial parotidectomy in cases with suspected metastasis, have been performed; however, sentinel lymph node mapping can drastically reduce the morbidity associated with unnecessary lymph node dissection.12 This technique has been shown to be of benefit in managing malignant melanoma of the ear due to its highly ambiguous and variable lymphatic drainage patterns.12

Sentinel node biopsy of the parotid gland can be performed as well with low morbidity and a high success rate.1 Byers et al6 suggested that neck dissections be reserved for patients with Clark level IV or V melanomas.

Immunotherapies

Immunotherapeutic agents, including interleukin-2 and interferon alpha 2b, have recently become significant adjuvant therapies for malignant melanoma, and investigation into a potential melanoma vaccine is currently underway.3 Consultations with surgical, medical, and possibly radiation oncology, nuclear medicine, and pathology may be needed in treating patients with malignant melanoma depending on tumor invasiveness and metastasis.

Evidence of metastatic spread should routinely be sought when examining patients. For patients with lesions <1 mm thick, close follow-up with biannual full-body skin examination is recommended for 2 years following excision, and subsequently each year for the next 8 years.3 Melanomas thicker than 1 mm may require up to 4 annual visits during the first 2 years, followed by biannual and annual exams. Chest x-ray is recommended annually during the first 5 years for lesions <3 mm thick, and biannually for those >3 mm thick.3

The patient’s follow-up

Our patient’s lesion was very superficial. Following excisional biopsy, a wedge excision with appropriate 10-mm margins was performed by a plastic surgeon. The result of the chest x-ray was normal. The patient is scheduled for follow-up examination every 6 months for 2 years and yearly thereafter.

Corresponding author

Amor Khachemoune, MD, CWS, Georgetown University Medical Center, Division of Dermatology, 3800 Reservoir Road, NW, 5PHC, Washington, DC 20007. E-mail: amorkh@pol.net.

1. Pockaj BA, Jaroszewski DE, DiCaudo DJ, et al. Changing surgical therapy for malignant melanoma of the external ear. Ann Surg Oncol 2003;10:689-696.

2. Swetter SM. Malignant melanoma. EMedicine 2003. Available at www.emedicine.com/derm/topic257.htm. Accessed on May 10, 2004.

3. Zalaudek I, Ferrara G, Argenziano G, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of cutaneous melanoma: a practical guide. SKINmed 2003;2:20-31.

4. Benmeir P, Baruchin A, Weinberg A. Rare sites of melanoma: melanoma of the external ear. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 1995;23:50-53.

5. Batsakis JG. Melanomas (cutaneous and mucosal) of the head and neck. In: Tumors of the Head and Neck: Clinical and Pathological Considerations. 2nd ed. Baltimore, Md, and London: Williams & Wilkins; 1980;431-447.

6. Byers RM, Smith JL, Russell N, et al. Malignant melanoma of the external ear. Review of 102 cases. Am J Surg 1980;140:518-521.

7. Davidsson A, Hellquist HB, Villman K, et al. Malignant melanoma of the ear. J Laryngol Otol 1993;107:798-802.

8. Hudson DA, Krige JEJ, Strover RM, et al. Malignant melanoma of the external ear. Br J Plast Surg 1990;43:608-611.

9. Eedy DJ. Surgical treatment of melanoma. Br J Dermatol 2003;149:2-12.

10. Lens MB, Dawes M, Goodacre T, et al. Excision margins in the treatment of primary cutaneous melanoma. A systemic review of randomized controlled trials comparing narrow vs. wide excision. Arch Surg 2002;137:1101-1105.

11. Narayan D, Ariyan S. Surgical considerations in the management of malignant melanoma of the ear. Plast Reconstr Surg 2001;107:20-24.

12. Wey PD, De La Cruz C, Goydos JS, et al. Sentinel lymph node mapping in melanoma of the ear. Ann Plast Surg 1998;40:506-509.

A 65-year-old farmer came to the office with a pigmented lesion on his left ear; the lesion had been there for about 2 years. He noticed different shades of black developing in the lesion during the previous 3 months.

On physical examination, we observed a 13 mm x 7 mm asymmetrical dark-brown-to-black papule, with pigment fading at its borders, on the lower helix of the patient’s left ear. No ulceration was noted.

As an incidental finding, we noted accumulation of a yellowish waxy material in the left retroauricular area. The right ear was normal on examination, and no mucosal lesions were found. Lymph nodes of the retroauricular, submandibular, occipital, and supraclavicular areas were normal. An excisional biopsy was performed.

What is the diagnosis?

How would you manage this case?

FIGURE 1

Pigmented papule on the ear

Diagnosis: Malignant melanoma

Our patient’s excisional biopsy, which included 3-mm lateral margins, demonstrated clear architectural and cytological abnormalities consistent with superficial spreading malignant melanoma. Pronounced anisocytosis with prominent nucleoli and unevenly distributed melanin was noted, with atypical melanocytes extending into the papillary dermis. The Breslow thickness was 0.55 mm (Clark level II), and the TNM stage was T1a.

Incidence of malignant melanoma

The incidence of malignant melanoma has more than tripled among Caucasians in the US over the last 40 years; it is the fastest-growing1 and seventh most frequent cancer in the country.2 The risk of developing malignant melanoma is expected to reach 1 in 50 by 2010,3 increasing from 1 in 250 less than a quarter-century ago.1 Elderly men are particularly at risk.

Roughly 20% of melanomas develop in the head and neck regions, and of these approximately 7% to 14% are located on the external ear.4 Melanoma of the external ear most frequently develops on the left side (possibly due to increased sun exposure while driving), usually on the helix.1,4 In a small series by Benmeir et al,4 most patients reported having had an ear nevus whose features (size, color) began changing before diagnosis. Of note, only about one quarter of cutaneous melanomas are discovered directly by physicians.3 Moreover, neoplasms in certain regions of the ear may easily go unnoticed, causing a delay in diagnosis and treatment.1

Lesions are generally found in peripheral areas of the ear and are usually the superficial spreading type; however, nodular melanoma predominated in 1 relatively recent series.7 The lack of subcutaneous tissue on the external ear may contribute to the ease of invasion and poor prognosis identified in several reports.4,7 Hudson et al8 noted more deeply penetrating and thicker lesions at presentation on the external ear in comparison with malignant melanoma of other head and neck areas.

Risk factors

Risk factors for developing malignant melanoma include intense intermittent sunlight exposure (primarily UVB) and blistering sunburns at an early age; skin types and certain ethnicities with limited tanning capability; personal or family history of melanoma; multiple nevi; and immunosup-pression.3 The vast majority of malignant melanomas arise de novo, although very rarely a nevus (usually a giant congenital melanocytic nevus) may undergo malignant transformation.3

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of malignant melanoma includes atypical nevi, dermatofibromas, lentigos, basal and squamous cell carcinomas, keloids and hypertrophic scars, and seborrheic keratoses.2

Making an accurate diagnosis

The ABCD approach

The ABCD approach to recognizing potentially malignant melanotic lesions is evaluation for Asymmetry, Border irregularity, Color variegation, and Diameter >6 mm (roughly pencil eraser size). Patients who report recent changes in the characteristics of existing nevi should be examined carefully.

Biopsy, histology, dermatoscopy

Excisional biopsy and histologic examination are required for diagnosis, which is facilitated by histochemistry and immunohistochemistry techniques. Architectural criteria are of greater diagnostic significance than cytologic features, rendering fine- needle aspiration or curettage less helpful and unnecessary for diagnosis.3 Before excision, corresponding areas of lymphatic drainage should be examined, and subsequently a full-thickness biopsy with 2- to 5-mm lateral margins should be performed.9

Dermatoscopy is an excellent noninvasive method for in vivo examination of suspected melanomas, being a potentially powerful resource for general practitioners and dermatologists alike. In this procedure, the suspected melanoma is covered with mineral oil, alcohol, or water and viewed with a hand-held dermatoscope, which magnifies from 10 to 100 times, allowing visualization of structures at and below the skin surface. In comparison with clinical analysis, the sensitivity of dermatoscopic diagnosis is increased by 10% to 30%.3

Management: Surgical excision and special considerations

Difficulties in managing ear melanomas arise due to the ear’s importance in daily functioning and to patient’s cosmetic concerns. Initial reports of malignant melanoma of the external ear indicated a poorer prognosis compared with lesions in other areas,5,6 but subsequent studies did not corroborate these findings.

Surgical excision

Surgical excision is the standard of care for malignant melanoma. The World Health Organization recommends excision margins of 5 mm for in situ lesions, and 20 mm for melanomas >2.1 mm thick,10 although treatment of external ear lesions must be individualized given the thin skin and various anatomic subdivisions of the ear. Pockaj et al1 found margins of at least 10 mm to be associated with the lowest recurrence risk.

Several techniques have been employed in lesion excision and postexcisional defect repair, including wedge resection, partial and total auriculectomy, wide excision and skin grafting, and Mohs micrographic surgery.4 Wedge resection was associated in 1 study8 with significantly increased melanoma recurrence when compared with wide local excision using 10-mm margins or total auriculectomy.

Skin and subcutaneous tissue should always be excised, but perichondrium is generally spared unless involved with the tumor.1 However, Narayan et al11 suggested cartilaginous excision in melanomas >1 mm thick, regardless of the presence of tumor infiltration. Various types of flaps are used in reconstructing surgical defects.11

Lymph node dissection

Elective lymph node dissection, as well as superficial parotidectomy in cases with suspected metastasis, have been performed; however, sentinel lymph node mapping can drastically reduce the morbidity associated with unnecessary lymph node dissection.12 This technique has been shown to be of benefit in managing malignant melanoma of the ear due to its highly ambiguous and variable lymphatic drainage patterns.12

Sentinel node biopsy of the parotid gland can be performed as well with low morbidity and a high success rate.1 Byers et al6 suggested that neck dissections be reserved for patients with Clark level IV or V melanomas.

Immunotherapies

Immunotherapeutic agents, including interleukin-2 and interferon alpha 2b, have recently become significant adjuvant therapies for malignant melanoma, and investigation into a potential melanoma vaccine is currently underway.3 Consultations with surgical, medical, and possibly radiation oncology, nuclear medicine, and pathology may be needed in treating patients with malignant melanoma depending on tumor invasiveness and metastasis.

Evidence of metastatic spread should routinely be sought when examining patients. For patients with lesions <1 mm thick, close follow-up with biannual full-body skin examination is recommended for 2 years following excision, and subsequently each year for the next 8 years.3 Melanomas thicker than 1 mm may require up to 4 annual visits during the first 2 years, followed by biannual and annual exams. Chest x-ray is recommended annually during the first 5 years for lesions <3 mm thick, and biannually for those >3 mm thick.3

The patient’s follow-up

Our patient’s lesion was very superficial. Following excisional biopsy, a wedge excision with appropriate 10-mm margins was performed by a plastic surgeon. The result of the chest x-ray was normal. The patient is scheduled for follow-up examination every 6 months for 2 years and yearly thereafter.

Corresponding author

Amor Khachemoune, MD, CWS, Georgetown University Medical Center, Division of Dermatology, 3800 Reservoir Road, NW, 5PHC, Washington, DC 20007. E-mail: amorkh@pol.net.

A 65-year-old farmer came to the office with a pigmented lesion on his left ear; the lesion had been there for about 2 years. He noticed different shades of black developing in the lesion during the previous 3 months.

On physical examination, we observed a 13 mm x 7 mm asymmetrical dark-brown-to-black papule, with pigment fading at its borders, on the lower helix of the patient’s left ear. No ulceration was noted.

As an incidental finding, we noted accumulation of a yellowish waxy material in the left retroauricular area. The right ear was normal on examination, and no mucosal lesions were found. Lymph nodes of the retroauricular, submandibular, occipital, and supraclavicular areas were normal. An excisional biopsy was performed.

What is the diagnosis?

How would you manage this case?

FIGURE 1

Pigmented papule on the ear

Diagnosis: Malignant melanoma

Our patient’s excisional biopsy, which included 3-mm lateral margins, demonstrated clear architectural and cytological abnormalities consistent with superficial spreading malignant melanoma. Pronounced anisocytosis with prominent nucleoli and unevenly distributed melanin was noted, with atypical melanocytes extending into the papillary dermis. The Breslow thickness was 0.55 mm (Clark level II), and the TNM stage was T1a.

Incidence of malignant melanoma

The incidence of malignant melanoma has more than tripled among Caucasians in the US over the last 40 years; it is the fastest-growing1 and seventh most frequent cancer in the country.2 The risk of developing malignant melanoma is expected to reach 1 in 50 by 2010,3 increasing from 1 in 250 less than a quarter-century ago.1 Elderly men are particularly at risk.

Roughly 20% of melanomas develop in the head and neck regions, and of these approximately 7% to 14% are located on the external ear.4 Melanoma of the external ear most frequently develops on the left side (possibly due to increased sun exposure while driving), usually on the helix.1,4 In a small series by Benmeir et al,4 most patients reported having had an ear nevus whose features (size, color) began changing before diagnosis. Of note, only about one quarter of cutaneous melanomas are discovered directly by physicians.3 Moreover, neoplasms in certain regions of the ear may easily go unnoticed, causing a delay in diagnosis and treatment.1

Lesions are generally found in peripheral areas of the ear and are usually the superficial spreading type; however, nodular melanoma predominated in 1 relatively recent series.7 The lack of subcutaneous tissue on the external ear may contribute to the ease of invasion and poor prognosis identified in several reports.4,7 Hudson et al8 noted more deeply penetrating and thicker lesions at presentation on the external ear in comparison with malignant melanoma of other head and neck areas.

Risk factors

Risk factors for developing malignant melanoma include intense intermittent sunlight exposure (primarily UVB) and blistering sunburns at an early age; skin types and certain ethnicities with limited tanning capability; personal or family history of melanoma; multiple nevi; and immunosup-pression.3 The vast majority of malignant melanomas arise de novo, although very rarely a nevus (usually a giant congenital melanocytic nevus) may undergo malignant transformation.3

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of malignant melanoma includes atypical nevi, dermatofibromas, lentigos, basal and squamous cell carcinomas, keloids and hypertrophic scars, and seborrheic keratoses.2

Making an accurate diagnosis

The ABCD approach

The ABCD approach to recognizing potentially malignant melanotic lesions is evaluation for Asymmetry, Border irregularity, Color variegation, and Diameter >6 mm (roughly pencil eraser size). Patients who report recent changes in the characteristics of existing nevi should be examined carefully.

Biopsy, histology, dermatoscopy

Excisional biopsy and histologic examination are required for diagnosis, which is facilitated by histochemistry and immunohistochemistry techniques. Architectural criteria are of greater diagnostic significance than cytologic features, rendering fine- needle aspiration or curettage less helpful and unnecessary for diagnosis.3 Before excision, corresponding areas of lymphatic drainage should be examined, and subsequently a full-thickness biopsy with 2- to 5-mm lateral margins should be performed.9

Dermatoscopy is an excellent noninvasive method for in vivo examination of suspected melanomas, being a potentially powerful resource for general practitioners and dermatologists alike. In this procedure, the suspected melanoma is covered with mineral oil, alcohol, or water and viewed with a hand-held dermatoscope, which magnifies from 10 to 100 times, allowing visualization of structures at and below the skin surface. In comparison with clinical analysis, the sensitivity of dermatoscopic diagnosis is increased by 10% to 30%.3

Management: Surgical excision and special considerations

Difficulties in managing ear melanomas arise due to the ear’s importance in daily functioning and to patient’s cosmetic concerns. Initial reports of malignant melanoma of the external ear indicated a poorer prognosis compared with lesions in other areas,5,6 but subsequent studies did not corroborate these findings.

Surgical excision

Surgical excision is the standard of care for malignant melanoma. The World Health Organization recommends excision margins of 5 mm for in situ lesions, and 20 mm for melanomas >2.1 mm thick,10 although treatment of external ear lesions must be individualized given the thin skin and various anatomic subdivisions of the ear. Pockaj et al1 found margins of at least 10 mm to be associated with the lowest recurrence risk.

Several techniques have been employed in lesion excision and postexcisional defect repair, including wedge resection, partial and total auriculectomy, wide excision and skin grafting, and Mohs micrographic surgery.4 Wedge resection was associated in 1 study8 with significantly increased melanoma recurrence when compared with wide local excision using 10-mm margins or total auriculectomy.

Skin and subcutaneous tissue should always be excised, but perichondrium is generally spared unless involved with the tumor.1 However, Narayan et al11 suggested cartilaginous excision in melanomas >1 mm thick, regardless of the presence of tumor infiltration. Various types of flaps are used in reconstructing surgical defects.11

Lymph node dissection

Elective lymph node dissection, as well as superficial parotidectomy in cases with suspected metastasis, have been performed; however, sentinel lymph node mapping can drastically reduce the morbidity associated with unnecessary lymph node dissection.12 This technique has been shown to be of benefit in managing malignant melanoma of the ear due to its highly ambiguous and variable lymphatic drainage patterns.12

Sentinel node biopsy of the parotid gland can be performed as well with low morbidity and a high success rate.1 Byers et al6 suggested that neck dissections be reserved for patients with Clark level IV or V melanomas.

Immunotherapies

Immunotherapeutic agents, including interleukin-2 and interferon alpha 2b, have recently become significant adjuvant therapies for malignant melanoma, and investigation into a potential melanoma vaccine is currently underway.3 Consultations with surgical, medical, and possibly radiation oncology, nuclear medicine, and pathology may be needed in treating patients with malignant melanoma depending on tumor invasiveness and metastasis.

Evidence of metastatic spread should routinely be sought when examining patients. For patients with lesions <1 mm thick, close follow-up with biannual full-body skin examination is recommended for 2 years following excision, and subsequently each year for the next 8 years.3 Melanomas thicker than 1 mm may require up to 4 annual visits during the first 2 years, followed by biannual and annual exams. Chest x-ray is recommended annually during the first 5 years for lesions <3 mm thick, and biannually for those >3 mm thick.3

The patient’s follow-up

Our patient’s lesion was very superficial. Following excisional biopsy, a wedge excision with appropriate 10-mm margins was performed by a plastic surgeon. The result of the chest x-ray was normal. The patient is scheduled for follow-up examination every 6 months for 2 years and yearly thereafter.

Corresponding author

Amor Khachemoune, MD, CWS, Georgetown University Medical Center, Division of Dermatology, 3800 Reservoir Road, NW, 5PHC, Washington, DC 20007. E-mail: amorkh@pol.net.

1. Pockaj BA, Jaroszewski DE, DiCaudo DJ, et al. Changing surgical therapy for malignant melanoma of the external ear. Ann Surg Oncol 2003;10:689-696.

2. Swetter SM. Malignant melanoma. EMedicine 2003. Available at www.emedicine.com/derm/topic257.htm. Accessed on May 10, 2004.

3. Zalaudek I, Ferrara G, Argenziano G, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of cutaneous melanoma: a practical guide. SKINmed 2003;2:20-31.

4. Benmeir P, Baruchin A, Weinberg A. Rare sites of melanoma: melanoma of the external ear. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 1995;23:50-53.

5. Batsakis JG. Melanomas (cutaneous and mucosal) of the head and neck. In: Tumors of the Head and Neck: Clinical and Pathological Considerations. 2nd ed. Baltimore, Md, and London: Williams & Wilkins; 1980;431-447.

6. Byers RM, Smith JL, Russell N, et al. Malignant melanoma of the external ear. Review of 102 cases. Am J Surg 1980;140:518-521.

7. Davidsson A, Hellquist HB, Villman K, et al. Malignant melanoma of the ear. J Laryngol Otol 1993;107:798-802.

8. Hudson DA, Krige JEJ, Strover RM, et al. Malignant melanoma of the external ear. Br J Plast Surg 1990;43:608-611.

9. Eedy DJ. Surgical treatment of melanoma. Br J Dermatol 2003;149:2-12.

10. Lens MB, Dawes M, Goodacre T, et al. Excision margins in the treatment of primary cutaneous melanoma. A systemic review of randomized controlled trials comparing narrow vs. wide excision. Arch Surg 2002;137:1101-1105.

11. Narayan D, Ariyan S. Surgical considerations in the management of malignant melanoma of the ear. Plast Reconstr Surg 2001;107:20-24.

12. Wey PD, De La Cruz C, Goydos JS, et al. Sentinel lymph node mapping in melanoma of the ear. Ann Plast Surg 1998;40:506-509.

1. Pockaj BA, Jaroszewski DE, DiCaudo DJ, et al. Changing surgical therapy for malignant melanoma of the external ear. Ann Surg Oncol 2003;10:689-696.

2. Swetter SM. Malignant melanoma. EMedicine 2003. Available at www.emedicine.com/derm/topic257.htm. Accessed on May 10, 2004.

3. Zalaudek I, Ferrara G, Argenziano G, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of cutaneous melanoma: a practical guide. SKINmed 2003;2:20-31.

4. Benmeir P, Baruchin A, Weinberg A. Rare sites of melanoma: melanoma of the external ear. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 1995;23:50-53.

5. Batsakis JG. Melanomas (cutaneous and mucosal) of the head and neck. In: Tumors of the Head and Neck: Clinical and Pathological Considerations. 2nd ed. Baltimore, Md, and London: Williams & Wilkins; 1980;431-447.

6. Byers RM, Smith JL, Russell N, et al. Malignant melanoma of the external ear. Review of 102 cases. Am J Surg 1980;140:518-521.

7. Davidsson A, Hellquist HB, Villman K, et al. Malignant melanoma of the ear. J Laryngol Otol 1993;107:798-802.

8. Hudson DA, Krige JEJ, Strover RM, et al. Malignant melanoma of the external ear. Br J Plast Surg 1990;43:608-611.

9. Eedy DJ. Surgical treatment of melanoma. Br J Dermatol 2003;149:2-12.

10. Lens MB, Dawes M, Goodacre T, et al. Excision margins in the treatment of primary cutaneous melanoma. A systemic review of randomized controlled trials comparing narrow vs. wide excision. Arch Surg 2002;137:1101-1105.

11. Narayan D, Ariyan S. Surgical considerations in the management of malignant melanoma of the ear. Plast Reconstr Surg 2001;107:20-24.

12. Wey PD, De La Cruz C, Goydos JS, et al. Sentinel lymph node mapping in melanoma of the ear. Ann Plast Surg 1998;40:506-509.

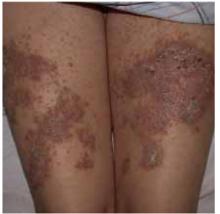

Chronic papules on the back and extremities

A 45-year-old Caucasian woman presented with pruritic erythematous scaling eruptions on her back and lower extremities. The patient said these skin lesions, which she has had since childhood, become worse in the summer. Additionally, her nails were fragile and often cracked. Her father and son had similar skin lesions.

On skin examination, we saw erythematous hyperkeratotic confluent papules and plaques on her back, chest, thighs, and lower legs. Multiple 3- to 5-mm keratotic papules were noted on the dorsa of her hands bilaterally. Fingernail examination revealed longitudinal lines with notching at the distal edges (Figures 1 and 2). Examination of other systems was unremarkable.

FIGURE 1

Papules on the back...

FIGURE 2

...and the thighs

What is your diagnosis?

Are any diagnostic tests Necessary to confirm it?

Diagnosis: darier’s disease

Darier’s disease, also called Darier-White disease or keratosis follicularis, is a genodermatosis that affects 1 in 55,000 to 100,000 persons.1 It is inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion, resulting from a mutation in chromosome 12q23-q24.1, which encodes the gene ATP 2A2, which in turn encodes a SERCA2 (sarco/endoplasmic reticulum calcium)-ATPase pump. This defect results in instability of desmosomes.2-4

With Darier’s disease, skin lesions are often present in the second decade of life but rarely appear in adulthood. The clinical findings are described as yellowish, greasy hyperkeratotic papules coalescing to warty plaques in a seborrheic distribution on the face, scalp, flexures, and groin. The nails can have red and white alternating longitudinal bands, as well as a V-shaped nicking at the distal nail plate, with resultant splitting and subungual hyperkeratosis. Oral and anogenital mucosa can have a cobblestone appearance. Some families have had associated cases of schizophrenia and mental retardation.1,5

The histologic findings on skin biopsies of Darier’s disease show acantholysis (loss of epidermal adhesion) and dyskeratosis (abnormal keratinization) as the 2 main features.

Laboratory tests: biopsy confirms diagnosis

Biopsy of a characteristic papule from the patient’s back revealed diffuse acantholytic dyskeratosis, which confirmed the clinical diagnosis of Darier’s disease.

Two types of dyskeratotic cells are present: corps ronds and grains. Corps ronds, found in the stratum spinosum, are characterized by an irregular eccentric pyknotic nucleus, a clear perinuclear halo, and a brightly eosinophilic cytoplasm. Grains are mostly located in the stratum corneum; they consist of oval cells with elongated cigar-shaped nuclei. The patient declined genetic testing.

Differential diagnosis

For hyperkeratotic plaques on the back and extremities, several diagnoses should be considered.

Psoriasis is a papulosquamous hyperproliferative disorder, with underlying autoimmune mechanisms.

Seborrheic dermatitis is another papulosquamous disorder involving the sebum-rich areas of the scalp, face, and trunk. In addition to sebum, is is linked to Pityrosporum ovale, immunologic abnormalities, and activation of complement.

Transient acantholytic dermatosis, or Grover’s disease, is a benign, self-limited disorder; however, it may be persistent and difficult to manage. The process usually begins as an eruption on the anterior part of the chest, the upper part of the back, and the lower part of the chest.

Familial benign pemphigus is a chronic autosomal dominant disorder with incomplete penetrance, which manifests clinically as vesicles and erythematous plaques with overlying crusts, which typically occur in the genital area, as well as the chest, neck, and axillary areas.

Management: retinoids, laser surgery

Therapeutic options are palliative. A multidisciplinary approach is often necessary; family physicians as well as dermatologists, and occasionally plastic surgeons, have important roles in managing this chronic condition.

Treatment options for Darier’s disease range from topical to systemic medications and laser therapies. Successful topical therapies include corticosteroids, retinoids, urea, salicylic acid, 5-fluorouracil, and topical antibiotics.5,6

The most successful treatment option is systemic use of retinoids, most often acitretin (Soriatane).1,5 This medication, like isotretinoin (Accutane), requires meticulous monitoring and counseling. Women of childbearing age should be instructed to use 2 birth-control methods and, according to current recommendations, instructed not to conceive for 3 years following cessation of treatment (2 years in Europe). Cyclosporine may be used to control acute, severe flares.

Laser excision, excision and grafting, and dermabrasion have been used to treat hypertrophic lesions.1,5 More recently, photodynamic therapy (using photosensitizers in conjunction with a source of visible light) was also used in the treatment of Darier’s disease.7

Keep in mind that patients with Darier’s disease are more susceptible to cutaneous infections with bacteria, herpes simplex virus, and poxvirus. Awareness of this susceptibility can facilitate early diagnosis and treatment.8

Corresponding author

Amor Khachemoune, MD, CWS, Georgetown University Medical Center, Division of Dermatology, 3800 Reservoir Road, NW, 5PHC, Washington, DC 20007. E-mail: amorkh@pol.net.

Submissions

Richard P. Usatine, Editor, Photo Rounds, University of Texas Health Sciences Center at San Antonio, Dept of Family and Community Medicine, MC 7794, 7703 Floyd Curl Drive, San Antonio, TX 78229-3900. E-mail: usatine@uthscsa.edu.

1. Goldsmith LA, Baden HP. Darier-White disease (keratosis follicularis) and acrokeratosis verruciformis. In Freedberg IM, Eisen AZ, Wolff K, Austen KF, et al, eds: Dermatology in General Medicine. 5th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 1999;614-618.

2. Jacobsen NJ, Lyons I, Hoogendoorn B, et al. ATP2A2 mutations in Darier’s disease and their relationship to neuropsychiatric phenotypes. Hum Mol Genet 1999;8:1631-1636.

3. Sakuntabhai A, Ruiz-Perez V, Carter S, et al. Mutations in ATP2A2, encoding a Ca+2 pump, cause Darier disease. Nat Genet 1999;21:271-277.

4. Ahn W, Lee MG, Kim KH, Muallem S. Multiple effects of SERCA2b mutations associated with Darier’s disease. J Biol Chem 2003;278:20795-20801.

5. Cooper SM, Burge SM. Darier’s disease: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and management. Am J Clin Dermatol 2003;4:97-105.

6. Knulst AC, De La Faille HB, Van Vloten WA. Topical 5-fluorouracil in the treatment of Darier’s disease. Br J Dermatol 1995;133:463-466.

7. Exadaktylou D, Kurwa HA, Calonje E, Barlow RJ. Treatment of Darier’s disease with photodynamic therapy. Br J Dermatol 2003;149:606-610.

8. Parslew R, Verbov JL. Kaposi’s varicelliform eruption due to herpes simplex in Darier’s disease. Clin Exp Dermatol 1994;19:428-429.

A 45-year-old Caucasian woman presented with pruritic erythematous scaling eruptions on her back and lower extremities. The patient said these skin lesions, which she has had since childhood, become worse in the summer. Additionally, her nails were fragile and often cracked. Her father and son had similar skin lesions.

On skin examination, we saw erythematous hyperkeratotic confluent papules and plaques on her back, chest, thighs, and lower legs. Multiple 3- to 5-mm keratotic papules were noted on the dorsa of her hands bilaterally. Fingernail examination revealed longitudinal lines with notching at the distal edges (Figures 1 and 2). Examination of other systems was unremarkable.

FIGURE 1

Papules on the back...

FIGURE 2

...and the thighs

What is your diagnosis?

Are any diagnostic tests Necessary to confirm it?

Diagnosis: darier’s disease

Darier’s disease, also called Darier-White disease or keratosis follicularis, is a genodermatosis that affects 1 in 55,000 to 100,000 persons.1 It is inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion, resulting from a mutation in chromosome 12q23-q24.1, which encodes the gene ATP 2A2, which in turn encodes a SERCA2 (sarco/endoplasmic reticulum calcium)-ATPase pump. This defect results in instability of desmosomes.2-4

With Darier’s disease, skin lesions are often present in the second decade of life but rarely appear in adulthood. The clinical findings are described as yellowish, greasy hyperkeratotic papules coalescing to warty plaques in a seborrheic distribution on the face, scalp, flexures, and groin. The nails can have red and white alternating longitudinal bands, as well as a V-shaped nicking at the distal nail plate, with resultant splitting and subungual hyperkeratosis. Oral and anogenital mucosa can have a cobblestone appearance. Some families have had associated cases of schizophrenia and mental retardation.1,5

The histologic findings on skin biopsies of Darier’s disease show acantholysis (loss of epidermal adhesion) and dyskeratosis (abnormal keratinization) as the 2 main features.

Laboratory tests: biopsy confirms diagnosis

Biopsy of a characteristic papule from the patient’s back revealed diffuse acantholytic dyskeratosis, which confirmed the clinical diagnosis of Darier’s disease.

Two types of dyskeratotic cells are present: corps ronds and grains. Corps ronds, found in the stratum spinosum, are characterized by an irregular eccentric pyknotic nucleus, a clear perinuclear halo, and a brightly eosinophilic cytoplasm. Grains are mostly located in the stratum corneum; they consist of oval cells with elongated cigar-shaped nuclei. The patient declined genetic testing.

Differential diagnosis

For hyperkeratotic plaques on the back and extremities, several diagnoses should be considered.

Psoriasis is a papulosquamous hyperproliferative disorder, with underlying autoimmune mechanisms.

Seborrheic dermatitis is another papulosquamous disorder involving the sebum-rich areas of the scalp, face, and trunk. In addition to sebum, is is linked to Pityrosporum ovale, immunologic abnormalities, and activation of complement.

Transient acantholytic dermatosis, or Grover’s disease, is a benign, self-limited disorder; however, it may be persistent and difficult to manage. The process usually begins as an eruption on the anterior part of the chest, the upper part of the back, and the lower part of the chest.

Familial benign pemphigus is a chronic autosomal dominant disorder with incomplete penetrance, which manifests clinically as vesicles and erythematous plaques with overlying crusts, which typically occur in the genital area, as well as the chest, neck, and axillary areas.

Management: retinoids, laser surgery

Therapeutic options are palliative. A multidisciplinary approach is often necessary; family physicians as well as dermatologists, and occasionally plastic surgeons, have important roles in managing this chronic condition.

Treatment options for Darier’s disease range from topical to systemic medications and laser therapies. Successful topical therapies include corticosteroids, retinoids, urea, salicylic acid, 5-fluorouracil, and topical antibiotics.5,6

The most successful treatment option is systemic use of retinoids, most often acitretin (Soriatane).1,5 This medication, like isotretinoin (Accutane), requires meticulous monitoring and counseling. Women of childbearing age should be instructed to use 2 birth-control methods and, according to current recommendations, instructed not to conceive for 3 years following cessation of treatment (2 years in Europe). Cyclosporine may be used to control acute, severe flares.

Laser excision, excision and grafting, and dermabrasion have been used to treat hypertrophic lesions.1,5 More recently, photodynamic therapy (using photosensitizers in conjunction with a source of visible light) was also used in the treatment of Darier’s disease.7

Keep in mind that patients with Darier’s disease are more susceptible to cutaneous infections with bacteria, herpes simplex virus, and poxvirus. Awareness of this susceptibility can facilitate early diagnosis and treatment.8

Corresponding author

Amor Khachemoune, MD, CWS, Georgetown University Medical Center, Division of Dermatology, 3800 Reservoir Road, NW, 5PHC, Washington, DC 20007. E-mail: amorkh@pol.net.

Submissions

Richard P. Usatine, Editor, Photo Rounds, University of Texas Health Sciences Center at San Antonio, Dept of Family and Community Medicine, MC 7794, 7703 Floyd Curl Drive, San Antonio, TX 78229-3900. E-mail: usatine@uthscsa.edu.

A 45-year-old Caucasian woman presented with pruritic erythematous scaling eruptions on her back and lower extremities. The patient said these skin lesions, which she has had since childhood, become worse in the summer. Additionally, her nails were fragile and often cracked. Her father and son had similar skin lesions.

On skin examination, we saw erythematous hyperkeratotic confluent papules and plaques on her back, chest, thighs, and lower legs. Multiple 3- to 5-mm keratotic papules were noted on the dorsa of her hands bilaterally. Fingernail examination revealed longitudinal lines with notching at the distal edges (Figures 1 and 2). Examination of other systems was unremarkable.

FIGURE 1

Papules on the back...

FIGURE 2

...and the thighs

What is your diagnosis?

Are any diagnostic tests Necessary to confirm it?

Diagnosis: darier’s disease

Darier’s disease, also called Darier-White disease or keratosis follicularis, is a genodermatosis that affects 1 in 55,000 to 100,000 persons.1 It is inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion, resulting from a mutation in chromosome 12q23-q24.1, which encodes the gene ATP 2A2, which in turn encodes a SERCA2 (sarco/endoplasmic reticulum calcium)-ATPase pump. This defect results in instability of desmosomes.2-4

With Darier’s disease, skin lesions are often present in the second decade of life but rarely appear in adulthood. The clinical findings are described as yellowish, greasy hyperkeratotic papules coalescing to warty plaques in a seborrheic distribution on the face, scalp, flexures, and groin. The nails can have red and white alternating longitudinal bands, as well as a V-shaped nicking at the distal nail plate, with resultant splitting and subungual hyperkeratosis. Oral and anogenital mucosa can have a cobblestone appearance. Some families have had associated cases of schizophrenia and mental retardation.1,5

The histologic findings on skin biopsies of Darier’s disease show acantholysis (loss of epidermal adhesion) and dyskeratosis (abnormal keratinization) as the 2 main features.

Laboratory tests: biopsy confirms diagnosis

Biopsy of a characteristic papule from the patient’s back revealed diffuse acantholytic dyskeratosis, which confirmed the clinical diagnosis of Darier’s disease.

Two types of dyskeratotic cells are present: corps ronds and grains. Corps ronds, found in the stratum spinosum, are characterized by an irregular eccentric pyknotic nucleus, a clear perinuclear halo, and a brightly eosinophilic cytoplasm. Grains are mostly located in the stratum corneum; they consist of oval cells with elongated cigar-shaped nuclei. The patient declined genetic testing.

Differential diagnosis

For hyperkeratotic plaques on the back and extremities, several diagnoses should be considered.

Psoriasis is a papulosquamous hyperproliferative disorder, with underlying autoimmune mechanisms.

Seborrheic dermatitis is another papulosquamous disorder involving the sebum-rich areas of the scalp, face, and trunk. In addition to sebum, is is linked to Pityrosporum ovale, immunologic abnormalities, and activation of complement.

Transient acantholytic dermatosis, or Grover’s disease, is a benign, self-limited disorder; however, it may be persistent and difficult to manage. The process usually begins as an eruption on the anterior part of the chest, the upper part of the back, and the lower part of the chest.

Familial benign pemphigus is a chronic autosomal dominant disorder with incomplete penetrance, which manifests clinically as vesicles and erythematous plaques with overlying crusts, which typically occur in the genital area, as well as the chest, neck, and axillary areas.

Management: retinoids, laser surgery

Therapeutic options are palliative. A multidisciplinary approach is often necessary; family physicians as well as dermatologists, and occasionally plastic surgeons, have important roles in managing this chronic condition.

Treatment options for Darier’s disease range from topical to systemic medications and laser therapies. Successful topical therapies include corticosteroids, retinoids, urea, salicylic acid, 5-fluorouracil, and topical antibiotics.5,6

The most successful treatment option is systemic use of retinoids, most often acitretin (Soriatane).1,5 This medication, like isotretinoin (Accutane), requires meticulous monitoring and counseling. Women of childbearing age should be instructed to use 2 birth-control methods and, according to current recommendations, instructed not to conceive for 3 years following cessation of treatment (2 years in Europe). Cyclosporine may be used to control acute, severe flares.

Laser excision, excision and grafting, and dermabrasion have been used to treat hypertrophic lesions.1,5 More recently, photodynamic therapy (using photosensitizers in conjunction with a source of visible light) was also used in the treatment of Darier’s disease.7

Keep in mind that patients with Darier’s disease are more susceptible to cutaneous infections with bacteria, herpes simplex virus, and poxvirus. Awareness of this susceptibility can facilitate early diagnosis and treatment.8

Corresponding author

Amor Khachemoune, MD, CWS, Georgetown University Medical Center, Division of Dermatology, 3800 Reservoir Road, NW, 5PHC, Washington, DC 20007. E-mail: amorkh@pol.net.

Submissions

Richard P. Usatine, Editor, Photo Rounds, University of Texas Health Sciences Center at San Antonio, Dept of Family and Community Medicine, MC 7794, 7703 Floyd Curl Drive, San Antonio, TX 78229-3900. E-mail: usatine@uthscsa.edu.

1. Goldsmith LA, Baden HP. Darier-White disease (keratosis follicularis) and acrokeratosis verruciformis. In Freedberg IM, Eisen AZ, Wolff K, Austen KF, et al, eds: Dermatology in General Medicine. 5th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 1999;614-618.

2. Jacobsen NJ, Lyons I, Hoogendoorn B, et al. ATP2A2 mutations in Darier’s disease and their relationship to neuropsychiatric phenotypes. Hum Mol Genet 1999;8:1631-1636.

3. Sakuntabhai A, Ruiz-Perez V, Carter S, et al. Mutations in ATP2A2, encoding a Ca+2 pump, cause Darier disease. Nat Genet 1999;21:271-277.

4. Ahn W, Lee MG, Kim KH, Muallem S. Multiple effects of SERCA2b mutations associated with Darier’s disease. J Biol Chem 2003;278:20795-20801.

5. Cooper SM, Burge SM. Darier’s disease: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and management. Am J Clin Dermatol 2003;4:97-105.

6. Knulst AC, De La Faille HB, Van Vloten WA. Topical 5-fluorouracil in the treatment of Darier’s disease. Br J Dermatol 1995;133:463-466.

7. Exadaktylou D, Kurwa HA, Calonje E, Barlow RJ. Treatment of Darier’s disease with photodynamic therapy. Br J Dermatol 2003;149:606-610.

8. Parslew R, Verbov JL. Kaposi’s varicelliform eruption due to herpes simplex in Darier’s disease. Clin Exp Dermatol 1994;19:428-429.

1. Goldsmith LA, Baden HP. Darier-White disease (keratosis follicularis) and acrokeratosis verruciformis. In Freedberg IM, Eisen AZ, Wolff K, Austen KF, et al, eds: Dermatology in General Medicine. 5th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 1999;614-618.

2. Jacobsen NJ, Lyons I, Hoogendoorn B, et al. ATP2A2 mutations in Darier’s disease and their relationship to neuropsychiatric phenotypes. Hum Mol Genet 1999;8:1631-1636.

3. Sakuntabhai A, Ruiz-Perez V, Carter S, et al. Mutations in ATP2A2, encoding a Ca+2 pump, cause Darier disease. Nat Genet 1999;21:271-277.

4. Ahn W, Lee MG, Kim KH, Muallem S. Multiple effects of SERCA2b mutations associated with Darier’s disease. J Biol Chem 2003;278:20795-20801.

5. Cooper SM, Burge SM. Darier’s disease: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and management. Am J Clin Dermatol 2003;4:97-105.

6. Knulst AC, De La Faille HB, Van Vloten WA. Topical 5-fluorouracil in the treatment of Darier’s disease. Br J Dermatol 1995;133:463-466.

7. Exadaktylou D, Kurwa HA, Calonje E, Barlow RJ. Treatment of Darier’s disease with photodynamic therapy. Br J Dermatol 2003;149:606-610.

8. Parslew R, Verbov JL. Kaposi’s varicelliform eruption due to herpes simplex in Darier’s disease. Clin Exp Dermatol 1994;19:428-429.